Cdl. McCarrick and the Conspiracy of the Well-Meaning

Teen’s Dying Wish to End Abortion, Save Lives

July 9, 2018

Saint of the Day for July 10: St. Veronica Giuliani (Dec. 27, 1660 – July 9, 1727)

July 10, 2018

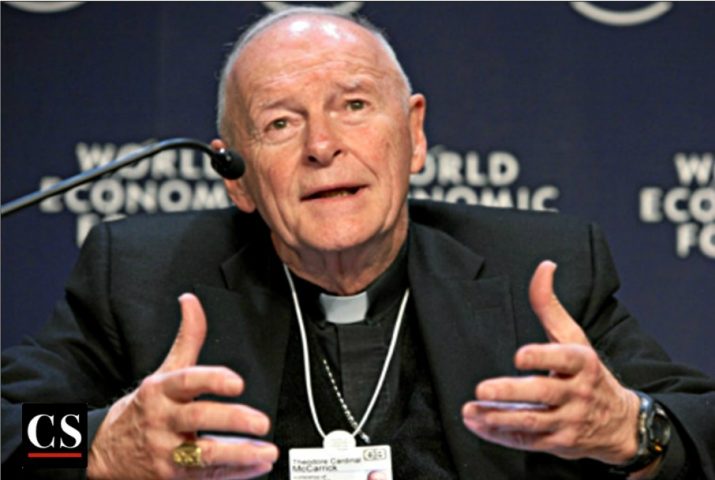

Photo: Cdl. Theodore E. McCarrick speaking at the 2008 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

By Anthony S. Layne, Catholic Stand, July 7, AD2018

If you ask me what I know of the accusations against the archbishop emeritus of Washington, D.C., Cdl. Theodore McCarrick, I must reply, very little. I know he’s accused of sexually abusing at least one minor and three adults; while accusation isn’t proof, the reports seem credible enough to take his guilt as a working hypothesis. The National Catholic Register reports accusations that Cdl. McCarrick’s “sexual misbehavior with seminarians and young priests was well-known to local journalists and Church insiders well before his appointment to Washington, D.C.” But, with one exception, no one would go on record with their accusations or suspicions.

If you ask me what I know of the accusations against the archbishop emeritus of Washington, D.C., Cdl. Theodore McCarrick, I must reply, very little. I know he’s accused of sexually abusing at least one minor and three adults; while accusation isn’t proof, the reports seem credible enough to take his guilt as a working hypothesis. The National Catholic Register reports accusations that Cdl. McCarrick’s “sexual misbehavior with seminarians and young priests was well-known to local journalists and Church insiders well before his appointment to Washington, D.C.” But, with one exception, no one would go on record with their accusations or suspicions.

Why Didn’t We Hear About This Sooner?

From what I’ve read, the publicly-known accusations well predate Cdl. McCarrick’s elevation to the Washington see (2000) and the red hat (2001). Yet somehow, they managed to evade the glaring light shone on the episcopate during the “Long Lent” of 2002, and even stayed under the radar for another 16 years. In that time, many other priests and at least one bishop have faced criminal and civil proceedings, some on dubious if not patently bogus allegations, and the moral authority of the Church in America has been crippled if not ruined. But Cdl. McCarrick’s past still didn’t make the front pages.

I doubt it was his position. After all, Bernard Law (may God have mercy on his soul) was also an archbishop of a major city and a cardinal prince of the Church. Yet this didn’t prevent the Boston Globe from exposing his role in covering up the abuses of Richard Geoghan, which led to Law’s resignation and removal to Rome.

One person sneered that “Uncle Ted” was “the Democrat Party voice in the Church,” his explanation for the media’s reluctance to expose Cdl. McCarrick. He was an advocate for migrants and refugees and raised funds for inner-city schools, which may have given him liberal street cred. But this line of reasoning becomes more dubious when combined with the claim that McCarrick was part of the so-called “lavender Mafia” trying to subvert from within the Church’s teaching on same-sex attraction. And it doesn’t explain why journalists whose desire to expose corruption is stronger than their desire to promote liberal causes would miss out or pass on this story.

Men and Sexual Victimization

One possibility is that, until the rack of allegations included a minor, the known predatory behavior was limited to only adult males. We operate on the presumption that rape and harassment happen only to women—except in prison—and that men’s willingness to have sex is practically a given, especially among gay or bisexual men.

But, as I’ve written elsewhere, that just ain’t so. The sexual victimization of men—including victimization by women—is vastly under-reported, and the incidence in both sexes is higher among the same-sex-attracted. The intersectionality paradigm trades on this stereotype; when men tried to participate in the #metoo movement, feminists tried to shut them down: “We’re talking about us, not you!” The perception that “Uncle Ted” was cavorting in gay bacchanalias rather than coercing unwilling young men to “cuddle” with him served political and social interests because it left the male and gay stereotypes untouched.

If you’re not a Catholic or at least a regular communicant and participant in your parish, then you, Dear Reader, may not realize just how deeply the scandals of 2002 have changed the Church in America. For instance, I had to take safety training when I became a Minister to the Sick last year. Since then, the diocese’s requirement has been extended to members of the Knights of Columbus since we lead and run so many parish activities. My experience is by no means singular or local; throughout the country, parishes and dioceses are becoming almost hyper-vigilant and intolerant concerning sexual abuse, to the point that it doesn’t take a very credible allegation to ruin a priest’s career.

But men aren’t supposed to be victims. We’re supposed to be able to defend ourselves. And to the extent that we have been victimized, we’re supposed to shut up, “put on our big-boy britches,” and just get over it. Those who don’t are wusses and snowflakes. And precisely because the concern focuses on the most vulnerable in our society, it does nothing to shatter the preconception that men can’t be sexually assaulted.

The McCarrick Conspiracy?

However, I’m not convinced the stereotype is a sufficient explanation. After all, those who were “in the know” knew there was a coercive, predatory element to Cdl. McCarrick’s activities. They were disturbed enough to talk to other people; for example, respected, high-visibility columnist Rod Dreher. Dreher relates that “a major magazine” killed a 2012 story that would have brought everything to light; did McCarrick really have that kind of pull? Or, as Dreher alleges, did other bishops “run cover for Ted McCarrick all these years”? Or is Dreher falling victim to the conspiracy-theorist mindset now plaguing our distrustful country?

For my own part, I try to adhere to “Hanlon’s razor”: Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity. Or, to put it less cynically, ordinary human fallibility suffices to explain why many bad things happen without the need to seek a conspiracy.

Nonetheless, there is a kind of conspiracy which we could call “the conspiracy of the well-meaning”: At times, people act in concert to prevent revelation of misdeeds, not because they feel they will be personally threatened or damaged by it, but because they think the revelation will do more harm than good, that there are other goods at stake which will be damaged or destroyed by public knowledge.

At the Heart of Injustice

Sometimes, they’re right. Many if not most state secrets fall into this category. The revelation of Geoghan’s predations and the Archdiocese’s virtual collusion devastated the Catholic Church in Boston, as other revelations desolated the Church in Ireland. “Let justice be done, though the heavens fall” is a great sentiment for those who won’t be crushed by the pieces or have to live in the wreckage.

But all too often, the “good” to be served by silence is an abstraction—the good of the Church, the faith of the people, public perception, the benevolence of non-Catholics. At the heart of every injury, every injustice, there lies the concrete reality of the human person that received the wound. The gospel message draws an equals sign between our relationships with other people and our relationship with God: whatever we do to others, we do to Him (cf. Matthew 25:31-46). The formal charitable institutions we run don’t take precedence over our obligation to deal justly with one another.

Whatever impact such revelations have “outside the walls,” it shouldn’t shake our own faith. If what we teach is true, then we should expect to find the Church contains hypocrites—those whose hearts are too hard or infertile for it to take root, those whose hearts are fertile yet allow the concerns of the world to choke it off, and even varying yields among those in whom it produces fruit (cf. Matthew 13:3-9; cf. Matthew 13:24-30, 47-50). We should even expect to find some hypocrites in front of the altar.

Nonetheless, to admit our leadership can be just as faulty as the rest of us is no excuse to leave predators in power. When we admit to injustice and seek to correct it, we testify to the truth of the revelation, not to its defect. By contrast, the more we seek to hide it, the worse the damage is when it’s finally revealed. The good of the Church is better served by the most proximate revelation of such sins.

Conclusion: A Misplaced Emphasis

I believe it was a combination of things that allowed Cdl. McCarrick’s misbehavior to go un-spotlighted: failures of moral courage, reliance on stereotypes, and not a little bit of denial. Most of all, it was the tendency of otherwise well-meaning people to misplace emphasis on abstract groups to the detriment of justice for individual people: “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few,” if you will. But the many and the few are made up of ones, each one of whom God loves entirely and without reservation, and each of whom we’re called to love as ourselves.

A final note: It was the “Long Lent” of 2002 that started me on the path to reversion. I’ve always known that the priesthood and hierarchy contained flawed, failing people. It would be nice if our leaders were all wise, good, and zealous for the faith. But do we have a right to expect it? I’d say we have a right to expect them to always do their best, no more. Nevertheless, Hilaire Belloc was right to observe that “no merely human institution conducted with such knavish imbecility would have lasted a fortnight.”

The Church has survived thousands of crooks, dunderheads, perverts, and bureaucrats in her long life. She will survive Ted McCarrick.

Photography: See our Photographers page.

About the Author: Anthony S. Layne

Born in Albuquerque, N. Mex., and raised in Omaha, Nebr., Anthony S. Layne served briefly in the U.S. Marine Corps and attended the University of Nebraska at Omaha as a sociology major while holding a variety of jobs. Tony was a “C-and-E Catholic” until, while defending the Faith during the scandals of 2002, he discovered the beauty of Catholic orthodoxy. He currently lives in Denton, Texas, works as an insurance agent and in-home caregiver, participates in his parish’s Knights of Columbus council and as a Minister to the Sick, and bowls poorly on Sunday nights. Along with Catholic Stand, he also contributes to New Evangelization Monthly and occasionally writes for his own blogs, Outside the Asylum and The Impractical Catholic.

http://www.catholicstand.com/cdl-mccarrick-conspiracy-well-meaning/