The Danger of the Attacks on the Electoral College, by Trent England (2019)

Called to Divide, Not ‘Dialogue’, by Eric Sammons

March 6, 2020

Young Priest Receives News of Fatal Disease, Offers Up Suffering in Reparation for Sin, by Wendy Royston

March 6, 2020

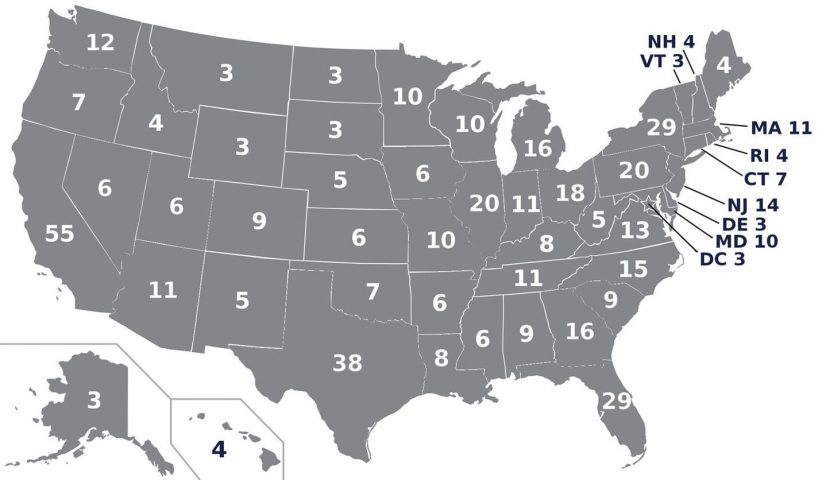

Electoral College, 2010. The U.S. Electoral College is made up of 538 members, representing all 50 states and the District of Columbia. States gain and lose electors based on Census data.

By Trent England, Director, Save Our States, Imprimis, June 2019, Volume 48, No. 6

The following is adapted from a speech delivered on April 30, 2019, at Hillsdale College’s Allan P. Kirby, Jr. Center for Constitutional Studies and Citizenship in Washington, D.C.

Once upon a time, the Electoral College was not controversial. During the debates over ratifying the Constitution, Anti-Federalist opponents of ratification barely mentioned it. But by the mid-twentieth century, opponents of the Electoral College nearly convinced Congress to propose an amendment to scrap it. And today, more than a dozen states have joined in an attempt to hijack the Electoral College as a way to force a national popular vote for president.

What changed along the way? And does it matter? After all, the critics of the Electoral College simply want to elect the president the way we elect most other officials. Every state governor is chosen by a statewide popular vote. Why not a national popular vote for president?

***

Delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 asked themselves the same question, but then rejected a national popular vote along with several other possible modes of presidential election. The Virginia Plan—the first draft of what would become the new Constitution—called for “a National Executive . . . to be chosen by the National Legislature.” When the Constitutional Convention took up the issue for the first time, near the end of its first week of debate, Roger Sherman from Connecticut supported this parliamentary system of election, arguing that the national executive should be “absolutely dependent” on the legislature. Pennsylvania’s James Wilson, on the other hand, called for a popular election. Virginia’s George Mason thought a popular election “impracticable,” but hoped Wilson would “have time to digest it into his own form.” Another delegate suggested election by the Senate alone, and then the Convention adjourned for the day. ….

Read more here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Electoral_College