Every San Franciscan — and every friend of freedom — should learn about Eugene Fahy, a native of Northern California who took a stand against tyrants and never backed down.

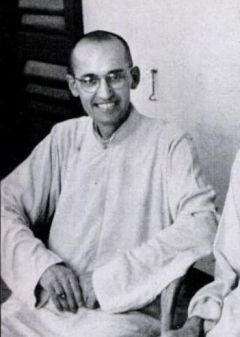

Born in San Mateo in 1911 and educated at Saint Ignatius and the University of San Francisco, Fahy was a brilliant man who left behind indisputable proof of his eloquence and courage. He could have been a prince of the city, one of San Francisco’s most prominent and prosperous men. Instead he took a vow of poverty and devoted his life to God.

He joined the Jesuits, went to China, was ordained a priest in Shanghai in 1945, and found himself in the district of Yangchow in 1949 — when the Communists arrived there.

Their first target: the Jesuit school.

“At first we were left pretty much alone while the Reds dug in,” Fahy wrote in a first-person account Life Magazine published in 1952 (and that is now available online).

“That summer, however, our school, the Aurora Preparatory, was taken by the Communists, both students and teachers being subject to an increasing barrage of dialectics,” he wrote.

They demanded “church reform.”

“Catholics were everywhere pressured to prove their ‘patriotism’ by cooperating,” wrote Fahy. “There were the naive few who thought it possible to concede an allowable inch when the Reds demanded a yard. Theirs was always the loss, and a bitter object lesson to a watching Church. Today it is now clear that there are but two choices: capitulation — or heroic defiance no matter what the cost.”

In Life Magazine, Fahy described how the Communists coopted a local “leader” then used intimidation and fear to bring others to the fold. Those who resisted — like Fahy and his fellow Jesuits — were destined for repeated interrogations in an ever-more brutal sequence of prisons.

A leading turncoat in Yangchow was a one-time principal of the Jesuit school.

“In February 1951, the ‘independence movement’ was inaugurated in Yangchow, the beginning for us of all that follows,” wrote Fahy. “The party, police and Board of Education had been seeking a pliable tool to open their attack. They found it in a former principal of Aurora and ex-Catholic named Lo Ping-yeh. He was an opportunist, a man who had collaborated too closely with the Japanese and who hoped to erase this stain by a like fawning before the new Red masters.”

With these new masters, the lackey called meetings of the “Reform Group.”

“To give the business a bit of weight, the head of the Board of Education pressed one of our teachers, Chu Shih Ch’ang to give a speech,” Fahy wrote. “Stubbornly silent until forced to make a statement, Chu finally admitted: ‘I don’t understand how it can be said that there is freedom of religion and at the same time freedom to attack religion. Perhaps you can enlighten me. It seems the equivalent to saying that a Chinese can love his country and not love his country at the same time.'”

The Communists and their newspapers did not report this accurately.

“Overnight, in true Communist fashion,” wrote Fahy, “his question, savagely distorted, became a statement: ‘A Chinese cannot love his country!’ There followed a rash of indignant articles in the local papers denouncing this ‘blasphemy.’ An accusation meeting was then called. Several hundred were in attendance, including some Catholics selected by name and forced to sit in front. Two of them fainted during the mad yelling and were finally allowed to return home. Chu Shih Ch’ang from then on was their man: to save himself he had to write out his accusations against us at least 10 times. His breakdown shook the other teachers. They began to fall in line.”

Lo Ping-yeh, the one-time Catholic principal, then called for the “Triple Autonomous Reform of the Yangchow Catholic Church.” Fahy and his fellow Jesuits were put in their first and most innocuous form of imprisonment — confinement to their residence.

Lo Ping-yeh then ordered Father Fahy — who as the prefect apostolic appointed by the pope was the leader of the Catholic Church in that region of China — to give up his religious authority. This, too, was brought before an “accusation meeting.”

“We were surrounded by the mob, as Lo Ping-yeh demanded that I relinquish my authority,” wrote Fahy. “I refused, again explaining the laws of the Church. But talk was vain. The crowd was now chanting in unison. ‘Give up your authority! Stop pretending!'”

“We could smell the hate,” said Fahy.

He and some other Jesuits — including Father William Ryan, who would later teach religion at San Francisco’s St. Ignatius — were then brought to the police station. Here the police chief questioned them.

“Patiently and laboriously I tried to make clear the distinction,” Fahy wrote, “that there was no problem involved in handing over church property but that on no account could I relinquish my spiritual authority to a group of schismatics.”

The Jesuits were then, by turn, incarcerated in an abandoned Carmelite monastery, a city jail and Shanghai prisons. Fahy was shackled, alone, in a small cell.

“It was a burial above ground in a vault of boards and bars, an animal wait in the numbing cold,” he wrote.

“Do you deny you’re a spy for the Vatican?” one of his inquisitors asked him. “Don’t you tremble to think what your American masters will do to you when you leave China?”

Yet the Communists did not break Monsignor Fahy. After 10 months, they freed him and his brother Jesuits.

Today, in Fahy’s home Archdiocese of San Francisco, some are calling for the removal of Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone, because he, like Fahy, will not back down from the teachings of the church.

“Evil may have its day, but to God go the weeks and the years,” wrote Fahy in 1952. “It must ever be so.”