Msgr. Charles Pope: 4 Errors You Should Avoid in the Proclamation of the Faith

June 12, 2018Patrick J. Buchanan: Behind Trump’s Exasperation

June 12, 2018

By Fr. George W. Rutler, Crisis Magazine, June 11, 2018

The recent pardon of the late world heavy weight champion Jack Johnson by our president was a gracious act long overdue. A previous motion had passed the House but died in the Senate in 2008. Johnson’s racially motivated conviction for violating the Mann Act after he had married a white woman resulted in his beginning a year term in Leavenworth prison in 1920. It was not a salutary place; I buried one of its inmates who had done much more than a year there. Johnson skipped bail and spent several years in Europe via Canada. In Barcelona, much in need of funds that had run out although he had garnered fantastic box office fees in illegal matches and had squandered them with commensurate prodigality, he undertook an exhibition match while on the lam in 1916. The site was a bullring near the church of Sagrada Familia. Johnson’s opponent was Arthur Cravan, a Swiss amateur boxer and Dadaist poet also in need of funds. The match was brief, as Cravan froze at the sight of the “Galveston Giant.” They fought by the eponymous rules of the Marquess of Queensbury, first published in 1867. As one of those curiosities only to be sorted out in the eternal habitations, the Marquess had brought the legal action leading to the downfall of Oscar Wilde, and Cravan was the nephew of Wilde. The atheist Marquess died ten months before Wilde, and both were received into the Catholic Church on their deathbeds.

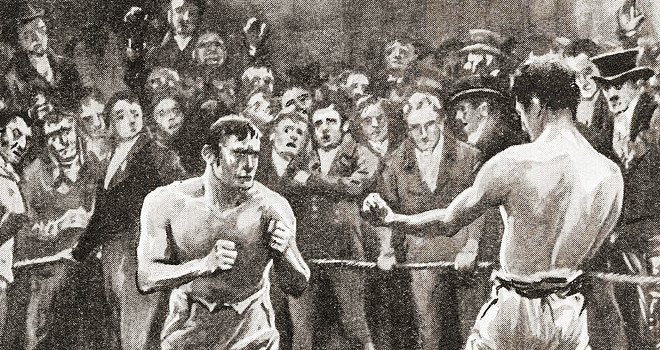

In Johnson’s early days, all professional boxing was illegal in the United States. His “Fight of the Century” against James Jeffries in 1910, and spectacularly captured on film, earned him over $1.7 million in today’s dollars, but it also caused a race riot. Because of the sullen unrest, Theodore Roosevelt urged that the film be censored: “The last contest provoked a very unfortunate display of race antagonism… and it would be an admirable thing if some method could be devised to stop the exhibition of the moving pictures taken thereof.” But Johnson’s success was a bit like Jesse Owens’s moral triumph at the Berlin Olympic games. Before that, in 1889, the monumental bout of John L. Sullivan (having quickly left Boston College where his Irish immigrant parents had placed him in hopes that he would become a priest) was fought against Jake Kilrain. Six state governors cooperated to see that the fight would take place with the law looking the other way. Hard to believe, the fight lasted seventy-rounds with bare knuckles, on a farm in Richburg, Mississippi, before a crowd of three thousand in temperatures above one hundred degrees, and the canvass was not innocent of blood. It took two hours and eighteen minutes. This still does not surpass the longest bare-knuckle fight at six hours and fifteen minutes between James Kelly and Jonathan Smith in Victoria, Australia, in 1855. Sullivan was befriended by Theodore Roosevelt and the president was coached by him, and continued to spar in the White House until a young artillery officer permanently blinded Roosevelt in one eye after a blow detached the retina of the 50-year-old chief executive. This was never disclosed to the public.

In 1945, raising money for war bonds, Jack Johnson managed to fight an exhibition match in New York City at the age of 67, consisting in three one-minute rounds each against Joe Jeanette and John Ballcourt. Exactly two years later, to the very month in the same Madison Square Garden, the disreputable fight manager Frank “Blinky” Palermo fixed the Jake LaMotta–Billy Fox fight. He is not to be confused with the Servant of God Joseph of Palermo, who before becoming a Capuchin had been expelled from several schools for punching some of his classmates. He is invoked as a patron of boxers and those with bad tempers, although the more commonly cited patron is Saint Nicholas of Myra because, perhaps with some embellishment of the narrative, he is said to have punched the heretic Arius at the Council of Nicaea in 325. Sancte Nicolae percute pro nobis.

The original Queensbury rules required gloves, but did not specify their weight. In early days they averaged just two ounces, compared with the ten to twelve ounces today. Some maintain that boxing gloves can inflict more harm because of more sustained punching, but forensic computer calculations estimate that bare knuckle fights have roughly 14,000 traumatic injuries per million blows measured against 76 per million with gloves.

If there is a sweetness in having one’s predictions vindicated, there is a bitter sweetness when the result is not good. So, for instance, I predicted in a volume published in 1971 when the ordination of women was only something of an academic speculation, that its character as a Gnostic misunderstanding would logically lead to attempts at marriage between the same sexes. At the time, this was ridiculed as some sort of absurd adynaton. My vindication is not happy because the result has been so sad. On a more banal level, I was criticized for warning in an article in Crisis Magazine in 2013 that legalization of Mixed Martial Arts would lead to worse coarseness. Alas, the unblushing oracle in me was right. Bare-knuckle boxing, which was never sanctioned in the United States, became approved when Wyoming became the first to legalize it on March 20 of this year at the behest of that state’s MMA Commission, one hundred and thirty years after John L. Sullivan pranced in the ring. The first match was shown live on Pay-Per-View television on June 2, broadcast from the Ice & Events Center in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Bare knuckle proponents claim that gloves were intended only to protect the hands, allowing the fighter to land more punches and throw harder, but the sanguinary scenes in Cheyenne disgraced the “sweet science” emblematic in the grace of fighters like Gene Tunney and Joe Lewis and their ranks of confreres.

At the tournament in Cheyenne, Bobby Gunn and nineteen other pros went at it. Reggie Burnette bloodied Travis “The Animal” Thompson. According to the Associated Press: “Arnold Adams, a 32-year-old MMA heavyweight, pounded ex-UFC fighter D.J. Linderman’s face into a bloody mess in front of 2,000 rowdy fans at a hockey rink that usually hosts birthday parties and skating lessons in Wyoming’s capital.” In the female division (at least femaleness is still considered an objective correlate) Bec Rawlings, a mother of two, attacked Alma Garcia in the second round on a technical knockout. The spectacle made female mud wrestling look like the Bolshoi Ballet.

I am not one to surrender boxing to the lesser sports, and I am on record as having participated ever so humbly in the ring myself. I helped to start what is now a bi-annual boxing exhibition match in my club in New York City, named for one of our former members, Teddy Roosevelt. I also know the importance of taping hands before putting gloves on, since one of my sparring partners fractured his fifth metacarpal, requiring surgery, because I had neglected to help tape his hand one inch up to the knuckles. But as some of my predictions in the past have been realized, I can anticipate that as our culture continues to devolve in ways beyond the worst fears of past pessimists, it is possible that legal bare knuckle boxing will lead to other games more despoiling of human dignity. If infants can be aborted and the elderly smothered, how is it impossible that the bloodlust of crowds in stadiums who watch men and women smash faces with their knuckles, will want to watch people stab each other and feed underlings to starved beasts as in days of old?

This, I grant, is possibly a theatric fear, but it is spoken with knowledge of colosseums where laureled civilizations thought that they had attained the apex of human achievement. In some respects the Roman Empire achieved greatly, but it also sported horribly. Their caesars included Lucius Arelius Commodus who imagined himself the reincarnation of Hercules, and entertained crowds by decapitating ostriches and killing cripples for entertainment. For any hyperbole, I apologize, but these people did exist and can exist again. The sadism of modern tyrants in the last century is proof enough of that. But another man also existed in conflicted Rome: the monk Saint Telemachus. According to the historian Theodoret, he jumped over a barrier into the middle of a gladiatorial arena in 391, tried to separate two of the fighters and shouted, “In the name of Jesus Christ, stop these wicked games!” The mob in the stands stoned him to death with the approval of the city prefect, but the emperor Honorius fell silent and then banned the gladiatorial spectacles. The last gladiator fought on January 1, 404.

© Copyright 2018 Crisis Magazine. All rights reserved.