Beyond the Fog of Politics, by Dr. Robert Royal

Msgr. Charles Pope: Recent Pro-Life Laws in Many States are Encouraging – But are There Dangers on the Road Ahead?

May 29, 2019

Leaked McCarrick Correspondence Confirms Vatican Restrictions, by Chad Pecknold

May 29, 2019

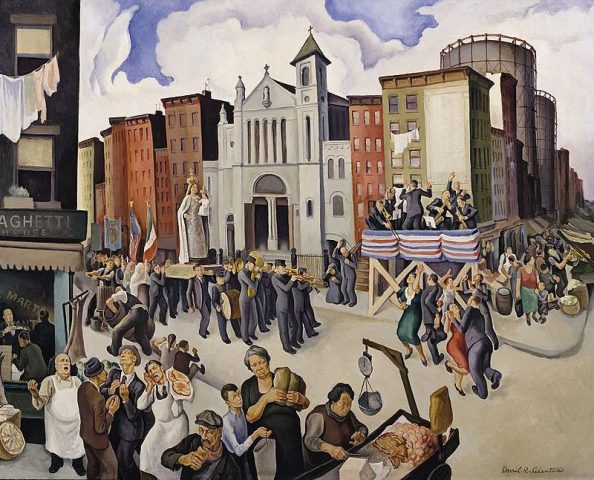

*Image: Festival by Daniel Celentano, 1934 [Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC]

By Dr. Robert Royal, Editor-in-chief, The Catholic Thing, May 29, 2019

![]() It’s not easy to interpret the recent European Union elections. Mainstream liberal and conservative parties lost considerable ground while “populists” and, in some countries, Greens showed strong gains. But the raw numbers call for careful parsing.

It’s not easy to interpret the recent European Union elections. Mainstream liberal and conservative parties lost considerable ground while “populists” and, in some countries, Greens showed strong gains. But the raw numbers call for careful parsing.

Pope Francis was clearly upset by the results. On Sunday, he released a message– not supposed to appear until four months from now, on the World Day of Migrants and Refugees (September 29) – sharply criticizing anti-immigrant sentiment in Europe, claiming that it reflects fear and racism, as well as failures in Christian charity and humanitarian engagement.

Welcoming the stranger and the refugee is, of course, a serious Christian obligation. And the pope is right to make sure that vulnerable people do not disappear from the world’s attention. But whether that general principle can be simply translated into national immigration policies – where other urgent questions also come into play – and whether the election results really stem from some lack of charity, is a far more debatable proposition.

The results actually reflect not only immigration questions, but other factors people in many nations are vaguely feeling: particularly alienation from “democratic” institutions, both national and international, which seem more to reflect the values and concerns of elites and less those of ordinary people.

That has been happening here in America as well as in countries from Australia to India, Brazil to the EU. It signifies, in various ways, departures from one of the most prominent modern dogmas: that global politics, particularly of a liberal and secularist cast, are a kind of established church (even for many in the Church).

Elite opinion assumes there must be something sinister, manipulative, quasi-fascist in the opposition to that orthodoxy. But this would be difficult to prove, since the phenomenon has arisen in quite different contexts worldwide, and now even on the most secularized and bureaucratized continent.

There may be dangers down the line from current nationalist sentiments, to be sure – not least resurgent anti-Semitism. But for now, the explanation for the success of these emerging political currents is that they attract voters, from various social sectors.

And just because they raise fundamental questions is not necessarily proof of anything. President Obama was applauded by elites when he spoke of “fundamentally transforming the United States of America.” Most modern nations now do need some basic re-ordering – as their peoples are saying quite clearly – though not necessarily in the direction Obama intended.

Pope Francis was probably most disappointed with the Italian results. The insurgent Lega of Matteo Salvini crushed all other parties with more than a third of the overall vote. The Lega’s coalition partner, Cinque Stelle, took 17 percent, and former Prime Minister Berlusconi’s Forza Italia 9 percent – 60 percent overall.

Meanwhile, the Partito Democratico, liberals similar to American Democrats, won only 20 percent, even though the Italian bishops have been demonizing Salvini and openly sympathizing with the PD. (Italian Catholics are often puzzled by this; the PD is the party of abortion and gay activism.)

Salvini also infuriated some bishops when he held up a Rosary towards the end of the campaign and affirmed that Catholicism undergirds his politics, which seek to limit immigration and strengthen Italian cultural solidarity.

As expected, Eastern Europe, where religion remains relatively strong, showed similar tendencies. In Hungary, Viktor Orban’s party received over 50 percent of the votes – the only surprise, a BBC commentator observed, was that the figure wasn’t even higher. Poland, the Slovak Republic, and other nations in the region showed smaller but significant shifts as well.

But motives vary. In some places – Britain and France notably, Germany as well – religion was a minor factor. The resistance there came more from a general cultural unease with loss of national identity and sovereignty – and resentment towards ruling elites who have contributed to that loss.

In the United Kingdom, the Brexit Party – formed only six weeks ago – took a third of the vote, about twice as many as the next party. Traditional parties – Labor and Conservatives – experienced a sharp downturn.

In France, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally – “far-right” to some observers – narrowly defeated President Emmanuel Macron’s Republic on the Move. That may appear unremarkable, but just two years ago, Macron – probably the single most prominent pro-EU political leader – was elected with 66 percent of French votes.

It would be irresponsible to see such massive shifts as some sort of sinister delusion. Immigration is part of it, another part is frustration about democratic forms being used to thwart popular sentiment.

And though little noticed, there’s also a growing sense that two fundamental views are now in conflict in many societies. In essence:

• Either, human beings are created and, therefore, free but dependent on acknowledging God and nature if they wish to flourish and find happiness,

• Or, human beings are random products of a meaningless, material universe, and such happiness as we shall find we have to create for ourselves (even if strict materialism renders human freedom an incoherent idea).

Liberal democracies were tolerable and viable when they still retained some connection, however tenuous, with the idea that they are rooted in God or nature that transcends the many conflicting individuals and groups in any society. That rootedness also affirms that people do not live in the abstract, but in concrete communities formed around shared values – not in openness to whatever zaniness has just escaped from college campuses.

Charles Péguy warned a century ago about our age: “this is the world of those without a mystique. . . .Let there be no mistake, and no one rejoice in it, on either side. The de-republicanization of France is essentially the same movement as the de-christianization of France. . . .It is one and the same movement which makes people no longer believe in the Republic and no longer believe in God, no longer want to lead a republican life and no longer want to lead a Christian life. One and the same sterility withers the city and Christendom.”

Today, you don’t need to be a genius or a prophet like Péguy to see that the older religious and civic virtues were interconnected – and now that they are separated, both are threatened. Politics alone will not heal the breach. But people instinctively sense how much is at stake. And seem to be voting accordingly.

*Image: Festival by Daniel Celentano, 1934 [Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC]