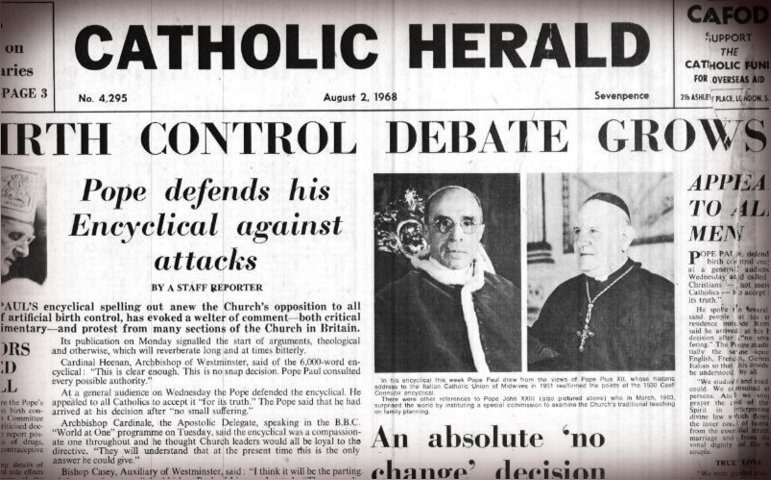

Photo: The Catholic Heralds front page after the encyclical was issued

After Paul VI released Humanae Vitae 50 years ago, Catholics split into warring tribes

By Stephen Bullivant, Catholic Herald, Thursday, 19 Jul 2018

For the philosopher Ralph McInerny, 1968 was “The Year the Church Fell Apart”. For Peter Steinfels, it saw the beginning of “the Vietnam War of the Catholic Church”. These apocalyptic descriptions – there are many more – refer to a single event: Pope Paul’s release on July 25, 1968, 50 years ago this week, of his encyclical on contraception, Humanae Vitae.

For the philosopher Ralph McInerny, 1968 was “The Year the Church Fell Apart”. For Peter Steinfels, it saw the beginning of “the Vietnam War of the Catholic Church”. These apocalyptic descriptions – there are many more – refer to a single event: Pope Paul’s release on July 25, 1968, 50 years ago this week, of his encyclical on contraception, Humanae Vitae.

Some writers have held Humanae Vitae responsible for the decline in Catholic practice over the past half-century: people either boycotted Mass in protest, or else became so frustrated and disillusioned with an institution (officially) committed to upholding its teaching that they ultimately gave up and left. Others suggest that Catholics drifted from the faith because of the unwelcoming reception the encyclical received from some bishops, priests, theologians and journalists. That “culture of dissent”, as Russell Shaw called it, is said to have weakened Catholic identity, and with it belief, practice and affiliation.

There is, however, another way to look at the aftermath of Humanae Vitae. But to understand the encyclical’s impact, we have to briefly revisit the events leading up to it.

In 1930 the Anglican Church’s Lambeth Conference permitted, albeit with heavy qualifications, the use of contraceptives. Meanwhile, growing numbers of American Protestant denominations did the same, often motivated by explicitly eugenic motivations. They began making their peace with contraception, if not for their own members, then at least for other, “undesirable” groups. In response, Pope Pius XI’s encyclical Casti Connubii bracingly reaffirmed that

… the Catholic Church, to whom God has entrusted the defence of the integrity and purity of morals, standing erect in the midst of the moral ruin which surrounds her, in order that she may preserve the chastity of the nuptial union from being defiled by this foul stain, raises her voice in token of her divine ambassadorship and through Our mouth proclaims anew: any use whatsoever of matrimony exercised in such a way that the act is deliberately frustrated in its natural power to generate life is an offence against the law of God and of nature, and those who indulge in such are branded with the guilt of a grave sin [my italics].

Three decades later, though, the issue had failed to go away. The growing women’s movement and the first stirrings of a sexual revolution; the invention of the Pill; increasing worries about Third World overpopulation; more publicity for the often tragic plight of Catholic parents faced with severe medical, domestic and/or economic pressures; greater social integration of Catholics with non-Catholics: it all meant that the pros and cons of birth control were much talked about by Catholics.

The one place where they weren’t talked about, however, was in the formal proceedings of the Second Vatican Council. In 1963, John XXIII lifted the issue of birth control out of the Council’s purview and entrusted it to a special committee. Its final report was finally released in 1966. This argued that modern hormonal contraceptive methods were not, in themselves, intrinsically opposed to Catholic sexual ethics. This report was leaked the following year, along with a dissenting opinion composed by a handful of the commission’s members, thus raising rampant expectations of change.

Famously, however, no change was forthcoming. When Paul VI finally released Humanae Vitae to the world, he fundamentally reaffirmed the basic position of Pius XI’s Casti Connubii.

The fallout – as Pope Paul half expected – was considerable. Priests criticised the encyclical from the pulpit. Formal letters and expression of dissent, signed by groups of clergy and theologians, began appearing immediately. The press joined in: the Daily Mail followed up a front-page splash on “The Pope’s Bitter Pill” by devoting much of page six to “Why we will defy the Pope: by the Catholic mothers taking the Pill”. Diocesan bishops were soon obliged to support the encyclical publicly, but often did so with a visible lack of conviction.

The nature of the controversy raises a question. It is not immediately obvious why Humanae Vitae should have prompted anyone to leave the Church who had not done so already. Is it really plausible to ascribe mass disaffiliation to Paul’s simple repetition, in a far kindlier tone than that used by his predecessors, of – in Mary Eberstadt’s words – “what just about everyone authoritative in the history of Christianity had ever said on the subject until practically the day before yesterday”?

Catholic couples wishing to space out or avoid pregnancies, after all, had always had two options: abstinence in one form or another, as the Church encouraged under some circumstances, or artificial contraception, with varying degrees of uneasy conscience. So it is not immediately obvious why Humanae Vitae should have prompted anyone to leave the Church who had not done so already. How could this issue suddenly become a deal-breaker?

There are two answers. First, there was a widespread expectation of change. The sheer fact that the topic was up for debate seemed to augur in this direction, as did the long time taken first by the commission, and then – especially once the commission’s conclusions were widely known – by the pope. Anticipating that Paul would ultimately adapt Church teaching, confessors increasingly began either explicitly to condone the practice, or else no longer to forbid it.

More significantly, there were large numbers of priests and theologians who had staked their reputations on knowledgeably second-guessing the pope. So when the expected change never materialised, it was surely not surprising that they would now double down.

Second, Catholics were by now used to things changing that had, only a few years before, appeared immutable. After all, if such totemic aspects of Catholic identity as Mass in Latin or fish on Fridays could change from one week to the next, if tabernacles and plaster statues of the Blessed Virgin could disappear from sight, if high altars could be abandoned in favour of cafeteria-style tables, and if altar rails could be ripped out altogether, what wasn’t susceptible to a radical overhaul? Thus Humanae Vitae led to surprise, followed by disappointment, frustration, disillusionment and even defiance.

But what proportion actually left in protest is not clear. No doubt there were some for whom Humanae Vitae was a contributor to their lapsing or perhaps joining another denomination. But those most deeply disappointed were practising Catholics, either already using birth control or anxiously awaiting permission to start, for whom the Vicar of Christ’s verdict was a very big deal. Precisely the kinds of people, that is to say, most likely to be highly committed Catholics with a heavy investment in Church teaching and practice. In the wake of the encyclical, such people were surely more likely to stay and work for change.

Nonetheless, this was a critical moment, because for many Catholics it changed their attitude to the Church’s authority. The cultural historian David Geiringer quotes one interviewee as saying: “It was the starting point really. I remember thinking, if the Church is wrong about this, it could be wrong about other things.”

But it is too simple to imagine Catholics suddenly rejecting all claims of “authority”, in favour of simply picking and choosing (“cafeteria Catholicism”). The controversy caused not so much a collapse of authority in the Church, as it did its fragmentation.

In practice, if not in theory, any religious group contains a complex of individual authorities. For Catholics, these include one’s parish priest, the half-remembered maxims of one’s teachers and catechists, the opinions in Catholic media and the views of various Catholic “experts”, including learned theologians, bishops and (sometimes) the pope.

If the “Catholic system” is working more or less as it ought to, there should be no meaningful disagreement between these various authorities. On most questions of faith and morals then, whatever one’s parish priest says should be at least consonant with whatever the pope himself would tell you.

In the wake of Humanae Vitae, however, this structure broke down. Under normal circumstances, Pope Paul’s “no” would have settled the question: even priests and theologians who thought the pope was wrong would have stopped saying so in public, either out of enlightened self-interest or (effectively) under duress. And lay Catholics who chose to continue doing the forbidden would do so quietly, and probably with an uneasy conscience.

Instead, for the reasons mentioned earlier, Humanae Vitae intensified the debate among Catholics. Many bishops clearly had little appetite either for defending the encyclical or disciplining their priests. For ordinary Catholics, it was hard to interpret the situation. For every bishop or theologian saying one thing, one was aware of at least some saying (or dog-whistling) the opposite.

For every parish homily in praise of the encyclical, there was another lamenting it. One Washington DC parish juxtaposed pro and contra homilies delivered at the same Mass, by the pastor and assistant pastor.

Both sides therefore felt that theirs was a legitimately Catholic position to hold. But the very fact that one could meaningfully talk in terms of “sides” is itself revealing. After Casti Connubii, there had been no serious question of what the “Catholic position” was on birth control. A Catholic who contradicted Pius XI, whether in thought, word or deed, was fully aware of the taboo nature of their position. But after Humanae Vitaethere was no longer a clear default position.

This is, therefore, the watershed moment at which tribal divisions between “liberal” and “conservative”, or “progressive” and “traditional” Catholics began to carry serious meaning. In the past, Catholics were typically divided into “good” and “bad’, or “practising” and “lapsed”. But these were, in a sense, degrees on a single scale of being Catholic. They were not two different modes, different camps, of being Catholic. In August 1968, to be fair, they weren’t either. But over the following years that is precisely what they would become.

Nor was this simply a matter of one’s position on Humanae Vitae – although 50-plus years later it would still serve as a pretty reliable litmus test. On the face of it, a person’s views on Humanae Vitae need not correlate in any predetermined way with their positions on various doctrinal points (women priests, say) or on their liturgical preferences. In practice, however, they very often do.

The immediate reaction to Humanae Vitae can, in retrospect, be seen as the opening skirmishes of the Catholic “culture wars”. But as so often, this was not purely a product of intra-Catholic dynamics. Even more important was the fact that in the wider cultures, social and moral attitudes were shifting dramatically, over divorce, abortion, gay rights and the changing role and status of women.

One place where the controversy really hit home was in the confessional. Priests took drastically different approaches, which reinforced the sense that the topic could not really be a matter of profound, salvation-or-damnation moral gravity.

How could something be an absolutely forbidden mortal sin in the confessional at 9.58am under Fr O’Malley, but at 10.02am, on Fr McMahon’s shift in the same confessional, be a topic left up to the couple’s own conscience and discernment?

A culture of “don’t ask, don’t tell” gradually emerged around contraception (and with it other sexual matters) in the confessional. This has now reached such an extent that today, according to my own informal polling of priests in Britain and America, the subject is rarely brought up either by the confessor or the penitent. Still more significantly, the practice of Confession itself very soon began a sharp freefall from which it has never recovered.

Humanae Vitae was not, it is true, the only possible contributor to this. The “Sacrament of Reconciliation”, as it was rebranded after the Council, suffered a great many experiments in pursuit of the ever-elusive “relevance”. Yet Pope Paul’s encyclical, and its aftermath, was certainly a major factor in a very significant change over the past 50 years: Catholics’ much-attenuated sense of sin, its life-or-death consequences and its sacramental remedies.

Stephen Bullivant is professor of theology and the sociology of religion at St Mary’s University, Twickenham, and a consulting editor of the Catholic Herald. This is an edited extract from the forthcoming book Mass Exodus: Catholic Disaffiliation in Britain and America since Vatican II (Oxford University Press, 2019)

This article first appeared in the July 20 2018 issue of the Catholic Herald. To read the magazine in full, from anywhere in the world, go here

For the philosopher Ralph McInerny, 1968 was “The Year the Church Fell Apart”. For Peter Steinfels, it saw the beginning of “the Vietnam War of the Catholic Church”. These apocalyptic descriptions – there are many more – refer to a single event: Pope Paul’s release on July 25, 1968, 50 years ago this week, of his encyclical on contraception, Humanae Vitae.

For the philosopher Ralph McInerny, 1968 was “The Year the Church Fell Apart”. For Peter Steinfels, it saw the beginning of “the Vietnam War of the Catholic Church”. These apocalyptic descriptions – there are many more – refer to a single event: Pope Paul’s release on July 25, 1968, 50 years ago this week, of his encyclical on contraception, Humanae Vitae.