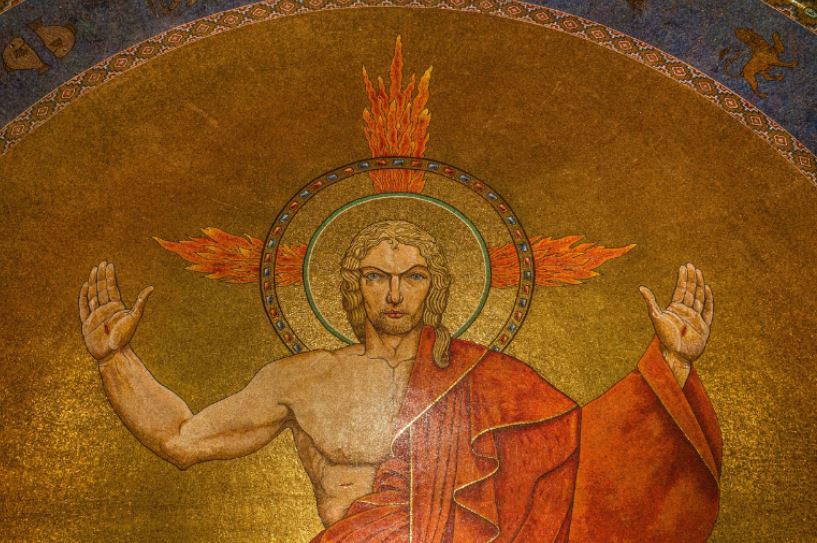

Photo: Under Xi Jinping, China has burned and bulldozed Catholic churches (Getty)

The Vatican’s agreement with Beijing signifies the abandonment of Vatican II’s political vision

By Matthew Schmitz, Catholic Herald, Thursday, 27 Sep 2018

Last week, the Vatican signed a concordat with a totalitarian regime. The Chinese government, which has harassed and tortured millions of Christians, will now have a role in selecting Catholic bishops. The agreement is provisional and the details are vague, but that much is clear.

Whatever one makes of the deal, it inarguably constitutes a break with the Church’s support of religious freedom as expressed in the Second Vatican Council. Before Vatican II, Church officials generally had not sought to secure freedom for the Church by appealing to neutral and broadly applicable principles of religious freedom. Instead, they signed concordats that granted the Church certain privileges, often in exchange for the authorities’ receiving some say in Catholic life.

The China deal is an agreement of this older kind. In exchange for a role in choosing bishops, China will effectively acknowledge the Pope’s authority over Chinese Catholics – something the regime has never before conceded.

Bishop Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo has defended the deal by claiming that China “observes the common good and it has proved its ability to great missions like fighting against poverty and pollution”. This is a novel way to describe the regime. According to a UN report in August, Chinese authorities are currently detaining a million people (out of a total population of 11 million) in the western province of Xinjiang, home to the Uighur Muslim minority. An additional two million people in the province are undergoing some form of re-education. Cadres monitor and report on every family. Cameras have been placed inside some homes.

Restrictions on religious life extend well beyond Xinjiang. Under Xi Jinping, the Chinese government has bulldozed and burned Protestant and Catholic churches. Gao Zhisheng, a Protestant human rights lawyer, released a book last year describing his torture at the hands of Chinese officials. They beat and electrocuted him before secretly imprisoning him in a camp, where he suffered further psychological torture. Gao calls the regime “totalitarian”. Unlike authors who apply that descriptor to Western governments, he was secretly detained following the book’s publication.

How could the Catholic Church make a deal with such a regime? Critics of the agreement have tended to present it as yet another blunder by Pope Francis. But it indicates a broader loss of confidence in the political vision of Vatican II.

After World War II, many Catholics concluded that concordats with Mussolini and Hitler had discredited the Church. Shame regarding these deals, combined with a certain optimism about the direction of history, led many to assert that a “free Church in a free society” was the future in the West and across the world.

Conservative Catholics trained their ire on socialist regimes, while liberal Catholics focused on right-wing dictatorships. But both used anti-totalitarian rhetoric to argue that the Church should stand on the side of liberty.

This outlook received its fullest expression in Vatican II’s Dignitatis Humanae, which suggested that the Church should support neutral religious liberties rather than seek privileges from the state. The Church continued to arrange concordats with smaller countries like Haiti and Vietnam, but broad-based defence of religious liberty was the ideal. The fall of the Berlin Wall seemed to vindicate the liberal belief that the world would turn toward freedom.

The China deal reflects a retreat from the political vision of the council fathers. Vatican II, which sought to disentangle Church and state, taught that the Pope alone should appoint bishops: “For the purpose of duly protecting the freedom of the Church and of promoting more conveniently and efficiently the welfare of the faithful, this holy council desires that in future no more rights or privileges of election, nomination, presentation, or designation for the office of bishop be granted to civil authorities.”

Popes had only gained this exclusive power of episcopal appointment at the end of the 19th century as liberal and secular states renounced the rights once claimed by Christian powers. In 1829, 555 of 646 bishops who recognised the Pope owed their appointments to the state. By the end of the Second Vatican Council, the Pope had almost untrammeled freedom in picking bishops.

Counter to expectations, this change did not create a hierarchy notable for courage and independence. As John O’Malley has observed, it made for an episcopacy that was “more docile in all spheres”. If bishops chosen by the Chinese state are supine before secular powers, if they lack apostolical courage, then they merely resemble their brother bishops in jurisdictions where the Church enjoys perfect liberty.

Some Catholic commentators have insisted that the agreement with China is not a concordat. Like Sánchez Sorondo’s minimisation of the Chinese regime’s crimes, this is an attempt to avoid facing reality. Church leaders can no longer pretend to be much purer or more committed to human rights than the authors of the Reichskonkordat. Without anyone noticing, the age of Catholic liberalism has come to an end.

Matthew Schmitz is senior editor at First Things and a Robert Novak journalism fellow