Sean Fitzpatrick: Never Tolerate Bad Apples

Christopher Altieri: The Vatican’s Photo Blunder Shows Media Reform is Still a Work in Progress

September 17, 2018

Regis Nicoll: Navigating the Confused State Of Manhood

September 17, 2018

By Sean Fitzpatrick, The Cardinal Newman Society, September 12, 2018

Today, Catholic children and young adults are assaulted by scandal—whether it’s in the behavior of their peers amid the prevailing culture, the poor example of elders, or revelations about the sins of certain priests and shepherds of the Church.

A good Catholic education or youth ministry will help shelter young people from some of this, focusing instead on what is True, Good, and Beautiful. This would be a valuable topic for the bishops to consider during their Synod on Young People next month.

But scandal creeps into the best Catholic homes and schools, and so faithful Catholic education must teach and exemplify a healthy response to sinful behavior. Perhaps Catholic teachers could help renew moral discipline and intolerance of evil in the Church.

This brings to mind the following story of a great saint and educator:

“Father, get up!”

Father Branda started from what he thought a dream. It had sounded so much like Don Bosco. Don Bosco was in Italy, of course, and not in his bedroom. It was 1886. John Bosco was indeed in Turin, leaving his Salesian College of Sarria, Spain, under Fr. Branda. Unbeknownst to Fr. Branda, however, some bad apples were at work beneath his nose.

One week later. “Father! Get up!” Don Bosco’s voice broke the nighttime stillness again. Fr. Branda sat bolt upright. Though not returned yet from Turin, Don Bosco stood before him, smiling through the shadows. “I see you are awake,” he said. Bewildered, Fr. Branda bounced out of bed, kicked into a cassock, and kissed the hand of his superior.

“Your house is bright,” Don Bosco said, “but there is a dark spot.” Suddenly Fr. Branda became aware of four men in the room. “Tell him to be prudent,” Don Bosco said, pointing to one. He then approached the other three, shifting like ghosts in the gloom. Fr. Branda knew these students and had often noted their sinister aspect and subversive attitude. “Expel these three immediately.”

These words uttered, Don Bosco vanished, and Fr. Branda found himself alone in his room. When the sun rose two hours later, Fr. Branda’s mind was racing with questions and doubts. Had he really seen Don Bosco that night? How could it be possible? And though he felt strongly that the three pointed out to him were a tainting influence, was he to expel them so suddenly, without any explicit evidence of wrongdoing?

Days passed. Still Fr. Branda had not done as he had been instructed. Continuing to mull over his mysterious experience, he received a letter from Turin from an Oratorian priest named Fr. Rua, in which he read with a pounding heart that Don Bosco had asked if Fr. Branda had carried out his order. Still Fr. Branda delayed.

Again, days passed. Fr. Branda was in the sacristy preparing to celebrate Mass. His heart remained troubled by the vision. He ascended the altar steps. He arranged the chalice. He descended and genuflected. He began the prayers at the foot of the altar. “If you do not expel those boys immediately as I ordered,” Don Bosco’s voice suddenly whispered in Fr. Branda’s ear, “this will be your last Mass.”

After Mass, Fr. Branda expelled the three boys. Though the grounds for their expulsion remain hidden to most, nothing is hidden to God or his holy ones.

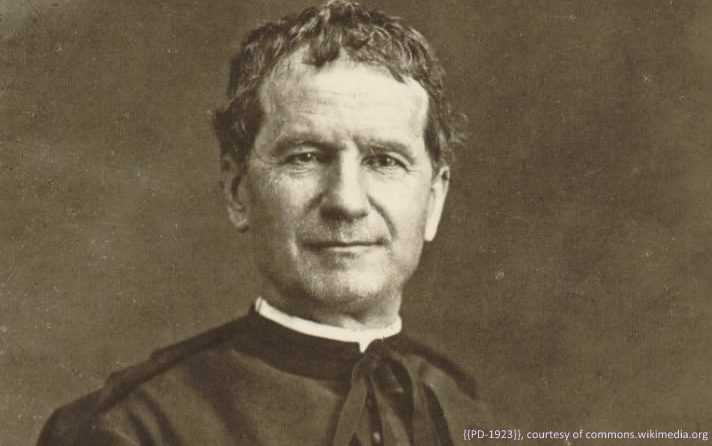

St. John Bosco was a holy teacher who loved his students, and, by his love, many souls were saved. But not all the souls Don Bosco loved were receptive of that love. And this can be the hardest part of a teacher’s vocation.

As any principal or headmaster knows, it is rarely easy to expel a student. Don Bosco, in his wisdom as a saintly educator, knew well the menace to the common good posed by those who refuse the good, and he never hesitated to expel those entrenched in sin or malice. He had no tolerance for those who resisted conversion and was swift to prevent their corruption from spreading. Though an unspeakably humble and generous priest, St. John Bosco knew the danger of tolerance when it came to evil, especially an evil attitude, and was never afraid to be intolerant when circumstances called.

The banner of “Tolerance” is one that flies all too proudly over the modern schoolhouse. Though a degree of tolerance is at times salubrious, too much of it can be suicidal. In the effort to accept, affirm, and acclimate, there exists a need to preserve cultural identity, rationality, spiritual integrity, and the natural order.

Culture without grounding is no longer culture—it is confusion. People cannot be themselves if they do not know who they are. St. John Bosco is a testament to the courage to be intolerant for the right reasons, even and especially when it comes to the student’s attitude. A major feature of being an upright member of any academic institution is attitude. Everything from manner to mindset should be assessed by those who uphold disciplinary standards, and rightly so.

The harmful consequences of a poor or negative attitude cannot always be pointed to precisely, which was what Fr. Branda struggled with, their cankered fruits being typically a cumulative poisoning of the school’s cultural climate which cannot be reduced to some single act, as other transgressions can be. They are, however, no less destructive than any mutiny. They are, perhaps, even more destructive in the long term because they can inculcate a bad will and a refusal to accept the spirit of a school, and a desire to damage the attitude of others. Any student who is judged as having a poor or subversive attitude, though they follow every rule, should be called to account.

The work of education largely depends on calling bad apples bad. May St. John Bosco guide us all, and especially all school administrators, as he guided Fr. Branda in choosing expulsion when expulsion was called for.

[Author’s note: Fr. Branda himself recounted the above story in writing and it is referenced also in Joan Carrol Cruz’s lives of the saints and Jeff Jansen’s book on miracles. The incident is held up by several scholars and storytellers as one of the instances of bilocation performed by St. John Bosco.]

SEAN FITZPATRICK is a graduate of Thomas Aquinas College and serves as the headmaster of Gregory the Great Academy in Elmhurst, Pa. He also serves on the Advisory Council for Sophia Institute for Teachers. His writings on education, literature and culture have appeared in Crisis Magazine, The Imaginative Conservative, and Catholic Exchange.