For part one of this series, see here.

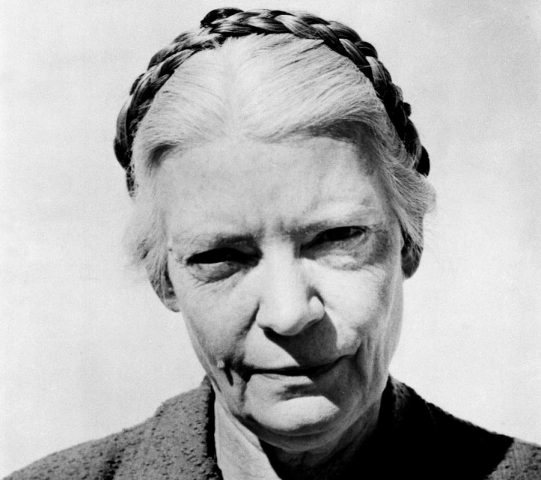

Early on in her memoir, The Long Loneliness (pp. 41-42), Dorothy Day remarks that even before she had encountered truly poor people, she had a visceral distaste for the middle class, for the staid and “comfortable” people she met in church, whom she saw as part of a system of exploitation and injustice. At the same time, she was drawn to society’s misfits and outcasts, to those who were oppressed by circumstances, and to those who willfully flouted social conventions. With a youthful sense of righteousness, she threw herself almost indiscriminately into radical causes, at times taking an overtly masochistic delight in the sufferings she endured.

Early on in her memoir, The Long Loneliness (pp. 41-42), Dorothy Day remarks that even before she had encountered truly poor people, she had a visceral distaste for the middle class, for the staid and “comfortable” people she met in church, whom she saw as part of a system of exploitation and injustice. At the same time, she was drawn to society’s misfits and outcasts, to those who were oppressed by circumstances, and to those who willfully flouted social conventions. With a youthful sense of righteousness, she threw herself almost indiscriminately into radical causes, at times taking an overtly masochistic delight in the sufferings she endured.

It was inevitable that such a self-dramatizing political dilettante would find herself entwined in organizations led (openly or secretly) by Communists — themselves expert at locating real injustices and exploiting them, as they did in the segregated American South. As her memoir expresses eloquently, in the midst of all this political and organizational energy, Day felt a deep spiritual void that sent her along many byways and that finally landed her inside the Catholic church. But she never overcame or even seemed to question her initial repugnance at people of property, at middle-class citizens who owned their businesses and strove to better themselves and their families.

The Communist movement which Day was serving was even then, at the same time, viciously persecuting the small landowners of Russia, especially in the Ukraine, driving them off the land and confiscating all their food, then deporting those who survived its terror famine to exile in the Gulag. Uncounted millions died for the “crime” of having tried to accumulate some wealth for their families. The Communist movement would go on, after Stalin’s alliance with Hitler soured and the Soviet Union conquered Eastern Europe, to savagely persecute the middle class in every country it acquired — from Hungary to Korea, China to Cuba.

Indeed, we could usefully compare the Communist hatred of property owners to the Nazi hatred of Jews, each of them partly fueled by the deadly sin of Envy. Although Day renounced the methods of Marxism, adopting a kind of anarchism that led her even to condemn the New Deal as too bureaucratic and impersonal, she never renounced her disdain for the middle class or the profit motive.

Nor did Day fully distance herself from communist sympathizers and activists, as one might expect a penitent Christian convert to do. In fact, throughout the mortal struggle the West waged from 1945 on against an aggressive communist empire now armed with nuclear weapons, Day counseled pacifism and called for the West to dismantle its nuclear weapons, unilaterally if need be.

When the United Nations intervened in 1950 to help the infant nation of South Korea fight off a savage, unprovoked invasion by the Stalinist puppet regime in Pyongyang, Day opposed American military aid to the beleaguered South Koreans. We can see today, in the freezing, starving, terrorized lives of North Koreans, what would have been the fate of South Koreans —and indeed, of all Europeans — had Americans been convinced by Day’s plea for “peace.” Perhaps that should count for something, when we consider the prospect of elevating Day as an example for every Christian. Of course, Day had previously opposed the U.S.defending itself against the Japanese and the Nazis after Pearl Harbor, so perhaps we should chalk up her stance in the Cold War to consistent, if delusional and irresponsible, pacifism.

“God Bless Castro”

Except that Day wasn’t consistent in her pacifism. Not entirely. Discussing Fidel Castro’s savage attacks on the Catholic Church during the Cuban revolution, she wrote of the situation in 1961 that “the church is functioning as normally as it can in our materialist civilization.” So things weren’t much worse than they were in, say, Chicago. Discussing Castro’s armed takeover, seizure of private property, and imposition of a Leninist one-party state, she commented:

We are certainly not Marxist socialists nor do we believe in violent revolution. Yet we do believe that it is better to revolt, to fight, as Castro did with his handful of men, he worked in the fields with the cane workers and thus gained them to his army — than to do nothing.

We are on the side of the revolution. We believe there must be new concepts of property, which is proper to man, and that the new concept is not so new. There is a Christian communism and a Christian capitalism as Peter Maurin pointed out. We believe in farming communes and cooperatives and will be happy to see how they work out in Cuba. We are in correspondence with friends in Cuba who will send us word as to what is happening in religious circles and in the schools. We have been invited to visit by a young woman who works in the National Library in Havana and we hope some time we will be able to go. We are happy to hear that all the young people who belong to the sodality of our Lady in the U. S. are praying for Cuba and we too join in prayer that the pruning of the mystical vine will enable it to bear much fruit. God Bless the priests and people of Cuba. God bless Castro and all those who are seeing Christ in the poor. God bless all those who are seeking the brotherhood of man because in loving their brothers they love God even though they deny Him.

Day wrote of North Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh, whose regime was equally as tyrannical and bloodthirsty as Castro’s, that she wished that the Catholic Worker could have “gained the privilege of giving hospitality to a Ho Chi Minh, with what respect and interest we would have served him, as a man of vision, as a patriot, a rebel against foreign invaders.”

I cannot help but wonder what people would make of a person who was driven by rabid patriotism to join the Nazi movement, who broke with it, but never denounced its supporters or reformed her attitude toward Jews, and who greeted the invasion of Poland with a call for pacifism and disarmament. Some might question how deep that convert’s conversion had gone. We must ask such questions about Dorothy Day, before we hold her up as a Christian example by making her a saint.

Day embraced the Christian tradition of lauding voluntary poverty and serving the poor — which has led many to compare her to St. Francis of Assisi. But there is one crucial contrast that needs to be pointed out. One of Francis’s early struggles was with an irrational fear and hatred of lepers. Indeed, upon his conversion, that sentiment was something that so shamed him that he made a special point of serving and treating lepers, even kissing their wounds.

Had Dorothy Day’s trajectory closely followed his, we might expect that she would have repented her long-time involvement in a movement that hunted and murdered middle-class people and property owners by the millions in a similar dramatic way. She might have mortified her ancient hatred by serving the despised bourgeoisie. Indeed, the most penitential, and therefore the most saintly, thing that Dorothy Day could have done would have been to minister to hard-working families in the suburbs. But this, she never did.

_______________________________

John Zmirak is a Senior Editor of The Stream, and author of the new Politically Incorrect Guide to Catholicism. He received his B.A. from Yale University in 1986, then his M.F.A. in screenwriting and fiction and his Ph.D. in English in 1996 from Louisiana State University. His focus was the English Renaissance, and the novels of Walker Percy. He taught composition at LSU and screenwriting at Tulane University, and has written screenplays for and with director Ronald Maxwell (Gods & Generals and Gettysburg). He was elected alternate delegate to the 1996 Republican Convention, representing Pat Buchanan.

He has been Press Secretary to pro-life Louisiana Governor Mike Foster, and a reporter and editor at Success magazine and Investor’s Business Daily, among other publications. His essays, poems, and other works have appeared in First Things, The Weekly Standard, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, USA Today, FrontPage Magazine, The American Conservative, The South Carolina Review, Modern Age, The Intercollegiate Review, Commonweal, and The National Catholic Register, among other venues. He has contributed to American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia and The Encyclopedia of Catholic Social Thought. From 2000-2004 he served as Senior Editor of Faith & Family magazine and a reporter at The National Catholic Register. During 2012 he was editor of Crisis.

He is author, co-author, or editor of eleven books, including Wilhelm Ropke: Swiss Localist, Global Economist, The Grand Inquisitor (graphic novel) and The Race to Save Our Century. He was editor of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute’s guide to higher education, Choosing the Right College and Collegeguide.org, for ten years, and is also editor of Disorientation: How to Go to College Without Losing Your Mind.

stream.org/dorothy-days-long-coziness-radical-left/

stream.org/dorothy-days-long-coziness-radical-left/

Early on in her memoir, The Long Loneliness (pp. 41-42), Dorothy Day remarks that even before she had encountered truly poor people, she had a visceral distaste for the middle class, for the staid and “comfortable” people she met in church, whom she saw as part of a system of exploitation and injustice. At the same time, she was drawn to society’s misfits and outcasts, to those who were oppressed by circumstances, and to those who willfully flouted social conventions. With a youthful sense of righteousness, she threw herself almost indiscriminately into radical causes, at times taking an overtly masochistic delight in the sufferings she endured.

Early on in her memoir, The Long Loneliness (pp. 41-42), Dorothy Day remarks that even before she had encountered truly poor people, she had a visceral distaste for the middle class, for the staid and “comfortable” people she met in church, whom she saw as part of a system of exploitation and injustice. At the same time, she was drawn to society’s misfits and outcasts, to those who were oppressed by circumstances, and to those who willfully flouted social conventions. With a youthful sense of righteousness, she threw herself almost indiscriminately into radical causes, at times taking an overtly masochistic delight in the sufferings she endured.