“Martha, Martha, you are anxious and troubled by many things.”

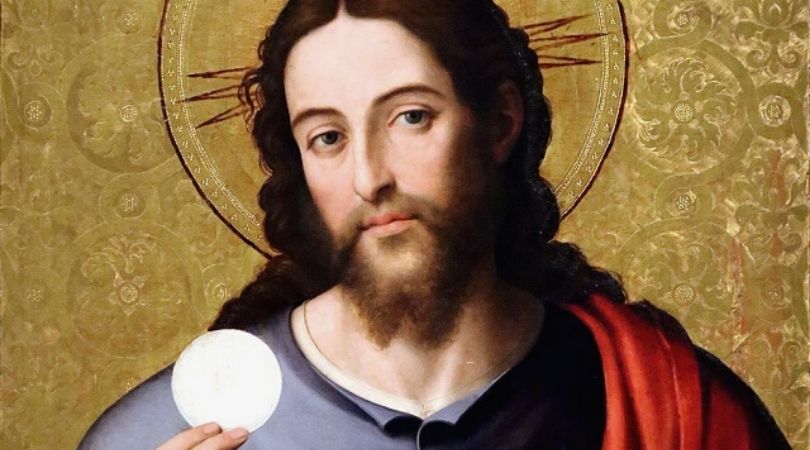

Illustration: Christ in the House of Martha and Mary by Jan Vermeer, 1654 [National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh]

By David Warren, The Catholic Thing, July 7, 2017

The words are flagged by Cardinal Sarah in his recent book, The Power of Silence, the English recension of which has finally fallen into my hands. The passage on Martha and Mary from Luke’s Gospel (10:41) is often cited today, by way of making an excuse.

“I am more like Martha,” I’ve heard too many times – often from a woman plausibly busy in the kitchen, or “multitasking” household, parental, marital, and a checklist of professional duties. She is run off her feet, in a peculiarly modern way, for the proliferation of labor-saving devices has added so much to our temporal burden, and to the requirements for speed. The little buzzers are constantly going off, and we are enslaved by everything from our kettles to our cell phones.

Sometimes I think the definition of a “soccer mom” is: a woman rolled and kicked about like a football. True, she is essential to the game, and is consistently returned to the center of it, but she is hardly appreciated in her own right. Others take the glory.

Even among women, others take the glory, and the primary achievement of feminism (it seems to me) has been to make women into inferior men, judging them by standards unmistakably masculine, then adding back functions unmistakably feminine (such as having babies) as mere pile-on.

The modern woman instinctively identifies with Martha, and has for all practical purposes been taught to do so not only by what remains of “society,” but by the contemporary Church struggling to be “relevant.” She is inclined to whine, sometimes, and when she comes upon this passage, she’s right there with Martha.

“I am more like Martha” – the saying may be droll. It may thus acknowledge a mite of self-criticism, for perhaps she has fallen behind in her “spiritual life”; and hasn’t yet made the brownies she promised to the church bake sale. (“Jesus is watching.”)

The Mary in this story is genuinely irritating, from Martha’s point of view – the life of prayer appears a life of ease – and when Our Lord takes Mary’s side, we have to accept it, yet with a flicker of resentment still. As one such Martha told me, “He is a typical male.”

One is supposed at least to smile knowingly. Yet even the capacity to make such a joke proves the criticism valid. For His Kingdom is not of this world, and here we invert that premise, supplanting what is most “important” with what seems more urgent, and must therefore be “prioritized.”

It is typical of Cardinal Sarah that he understands Christ’s remark. In his priorities, being precedes doing, and when Christ says, “Mary has chosen the good portion,” He is not making an invidious comparison. He does not deny that household work needs doing, or depreciate it. He (Christ, the Church Fathers, all consecrated priests, and this bishop combined in persona Christi) is saying that we must be Mary before we play Martha.

This is not a hard saying, but hard to understand for the modern mind which is, after all, quite distracted, and does not pause to consider things, in the silence that is the condition for contemplation of any kind. We think, to be sure, but only on our feet, when the better part is to think first kneeling. It is what makes modern domestic life so much resemble a situation comedy:

In reality, Jesus seems to sketch the outlines of a spiritual pedagogy: we should always make sure to be Mary before becoming Martha. Otherwise, we run the risk of becoming literally bogged down in activism and agitation, the unpleasant consequences of which emerge in the Gospel account: panic, fear of working without help, an inattentive interior attitude, annoyance like Martha’s towards her sister, the feeling that God is leaving us alone without intervening effectively.

As an old editor, I was distracted by my desire to hack through the translator’s clichés in the two sentences just quoted, and strip out the unnecessary words, starting with “literally.” My comment would be that they add unnecessary noise. But my own gnawing counsels of perfection must retreat before the plain substance.

For here, as in many hundred places in the Reverend Father’s book – produced with the help of a journalist, but with the clatter of his questions mostly suppressed – a real criticism is being leveled against “Martha,” writ large.

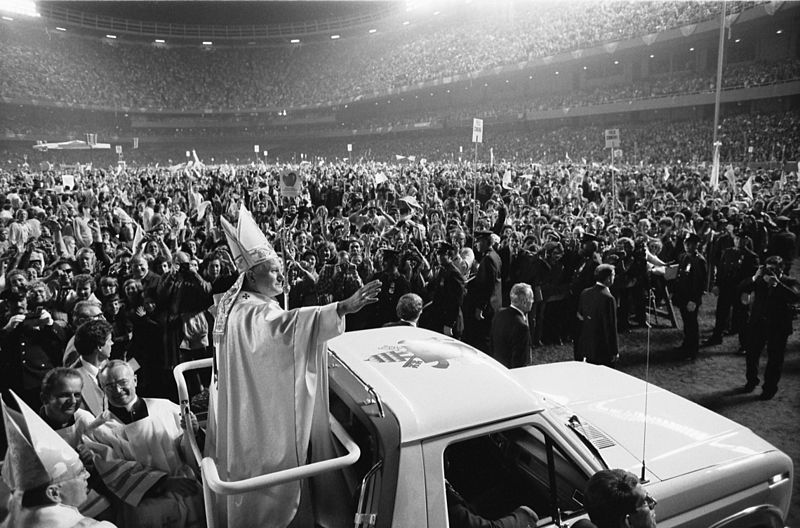

Cardinal Sarah continues the mission of Saint John Paul II, and Benedict XVI, to restore the possibility of Silence, in the face of Mystery, to what was becoming (long before Pope Francis) the Church of Martha.

We should not abandon many worldly causes – we cannot stop making lunch – but our tasks are not, finally, worldly. We must feed the poor, care for the ill, visit the prisoner, clean the environment, but these tasks are extrinsic to our sacramental core. First, we must actually be Christian, in conversation with Our Lord; and God speaks to us through silence.

Later, in some of the most poignant passages of the book, the Cardinal directly confronts the question that most vexes the modern mind. Why does God remain silent in the presence of misery and evil; why does He allow the horror and suffering that falls on the just and the unjust alike? If He is there, why doesn’t He do something?

This is, I think, the essential Martha question, expanded to become “inclusive” of the whole human condition.

To phrase the question more exactly, why must we participate in the God Man’s pain, in order to participate in His love? Phrased this way, the question begins to answer itself.

In the silence, kneeling before the Crucifix, the mystery of God’s love is articulated, through His Church, like the mystery of a mother’s love for her sick child. Though she seems to do nothing, in our agony, she is there.