By Michael J. Ortiz, Crisis Magazine, April 2, 2018

Each year, five million tourists view the 5000 square feet of Michelangelo’s amazing frescoes in the Sistine Chapel in Rome which depict Biblical scenes from the Fall to the Last Judgment. The Cappella Sistina is one of the great patrimonies of humanity. It doesn’t argue with you. It engulfs you in its momentous beauty.

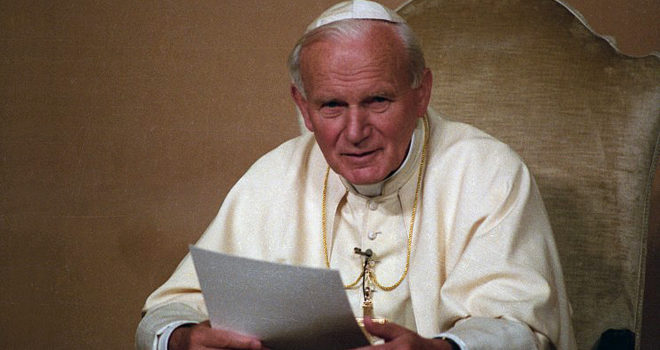

On this anniversary of his death, I would like to suggest that a single work of Pope John Paul II may be compared, in its significance and momentous insights, to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, though it be a fresco in words, as it were, not paint. In it, the lights and shadows of human dignity, our capacity for good and evil, are boldly drawn.

There are many facets to the Polish pope’s achievements recognized since his death in 2005. These include politics (the rise of Solidarity in his homeland; the fall of the Soviet Empire), the arts (his reflections on beauty, his earlier work as a poet and playwright), philosophy (his writings on the relationship between faith and reason), and naturally, theology (his triptych of encyclicals on the nature of God). John Paul led a long, active life, rooted in prayer, and the results, though not perfect, are there for all to see. If they look. Or read, that is.

Amidst these achievements which mark his long life, I think the central gift to the world of this philosopher-pope is his reflection on the nature of the moral act. Admittedly, not a riveting topic of conversation for most of us. Yet it is how we become who we are, in the inmost recesses of our being.

It’s all found in Veritatis Splendor, the Splendor of Truth, published in the fall of 1993, almost a quarter of a century ago. The bishops at Vatican II (1962-65) tried but failed to produce a document on moral theology before the storm of the 1960s broke. But with the help of Joseph Ratzinger (the future Pope Benedict XVI) and others, John Paul succeeded in fashioning the most significant official Church document on moral theology in over four hundred years.

Why so? When Pope Paul VI in 1968 continued to assert the constant teaching of the Church on the immorality of contraception, dissent became the order of the day for Catholics as the rest of the world blissfully embraced the so-called Sexual Revolution. The tragic results in broken families, for one thing, and in the easy reach of pornography, for another, are still with us today.

Some of the formulations of Catholic teaching from mid-century or earlier failed to convince the Aquarius generation and their descendants (in short, us). John Paul knew from his days as a university professor in Poland that a solid grounding in Christian anthropology, illuminated by faith, was desperately needed. So he provided us one, sketched out in fidelity to biblical sources and the Church’s perennial teaching over two millennia.

John Paul’s Veritatis Splendor voices the cry of rebellion and hope of every soul that ever suffered rather than do evil. He speaks with the great moral conscience of the best of our humanity, enlightened by grace. He shuts the door to every government that would make expedience its gospel, he disavows convenience before truth, before trust in the light given to every soul made in the image of God.

This Polish pope, his hair white as Santa Claus in his later years, has reminded us all that there are some things that should never be done. There are, whether we like it or not, “intrinsically evil” acts, always, and in themselves, regardless of our best intentions, regardless of the circumstances.

For those who maintain that this isn’t pastorally sensitive, how can hiding the truth about such central human concerns help anybody? How can abandoning the moral legacy of saints and martyrs and Holy Doctors lead anyone from the darkness of sin to the light of grace, that is, intimate friendship with the Lord God? This is why Vatican I’s admonition is perennially relevant: “the meaning of the sacred dogmas is ever to be maintained which has once been declared by Holy Mother Church, and there must never be any abandonment of this sense under the pretext or in the name of a more profound understanding.”

It appears that many Catholics have lost sight of this precious teaching. This is unfortunate on a number of levels, not least of which is that it gives the impression that the Church is arbiter of such realities, when she certainly is not. As Blessed John Henry Newman wrote, “though the Pope come of Revelation, he has no jurisdiction over nature.” (Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, Section Five)

Some scholars say that the image of God the Father reaching out to Adam on the Sistine ceiling is in the shape of a human brain, God bequeathing to humanity the light of intellect in a single, intimate touch. If we would ponder John Paul II’s teaching, we should see with equal clarity how every person we meet is called to be God’s masterpiece, a fresco for eternity, where any shadows of sin repented of and forgiven will only make the light more radiant.

(Photo credit: CNA / L’Osservatore Romano)