Vigano: Complaints of Homosexual Abuse Filed Against Msgr. Walter Rossi, by Christine Niles

June 17, 2019Daily Reading & Meditation: Tuesday (June 18)

June 18, 2019

By Christopher Altieri, Catholic Herald, 13 June, 2019

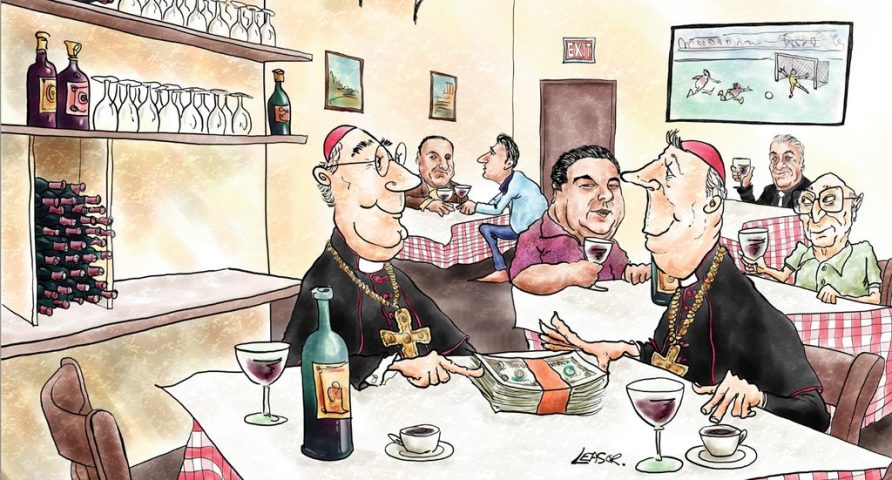

A new report gives a disturbing insight into the way that money circulates among Church leaders. How long can it continue?

“The Devil always enters by way of the pocket.” It’s a phrase that Pope Francis often repeats. He has it on no lesser authority than that of St Paul the Apostle, who wrote: “For the desire of money is the root of all evils; which some coveting have erred from the faith, and have entangled themselves in many sorrows” (1 Timothy 6:10).

If the allegations against Michael J Bransfield, the former Bishop of Wheeling-Charleston, as well as those regarding the scores of clerics who benefitted from his largesse, are correct, it would suggest that too many in the hierarchical leadership of the Church do not believe St Paul in any meaningful sense of the word, or else have become so used to an unseemly cultural reality that their good sense has been almost totally eclipsed.

First reported by the Washington Post last week, the story of Bishop Bransfield is one in which a man supposed to be a shepherd used the special circumstances of the diocese he led – specifically an enormous endowment grown out of a bequest of oil-rich land holdings in Texas nearly a century ago – to lead a lavish lifestyle.

An investigation concluded that he engaged “in a pattern of excessive and inappropriate spending” on such items “as personal travel, dining, liquor, gifts and luxury items”. Fresh flowers were reportedly delivered daily to his chancery office, at a total cost of $182,000 (£143,000) over 13 years. Investigators also accused him of sexual harassment.

(Bishop Bransfield has denied the allegations. He told the Washington Post last week that “none of it is true” and claimed that “Everybody’s trying to destroy my reputation”.)

The Washington Post reported that Archbishop William E Lori of Baltimore, the man the Vatican asked to lead the preliminary investigation into Bransfield, was one of the dozens of prelates to whom he would occasionally send monetary gifts. Bransfield would write cheques to clerics drawn on his personal account, and then have himself reimbursed out of diocesan coffers.

Archbishop Lori did not disclose these gifts to the Vatican at the time he agreed to lead the investigation. When the news was about to become public, he made restitution to the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston of the $7,500 (£5,900) in gifts he received. He also professed ignorance of Bransfield’s modus operandi and insisted that he had always acted in good faith.

Since the story broke, several other clerics – including Cardinal Kevin Farrell of the Dicastery for Laity, Family and Life, who had benefited to the tune of $29,000 (£23,000), seemingly for renovations to his Rome apartment – have announced they will return money they received from Bishop Bransfield. But why only do so when the gifts became public, rather than refusing them in the first place?

This is all coming out despite the Church’s investigation, not because of it. Indeed, the impression one gets from bishops’ public statements is that very few of them thought anything was strange about the money going around. It’s just what high churchmen do, at least in the US.

This story’s details have been widely reported. There is no reason to rehearse them here, other than to find and articulate a way to understand the current cultural moment in the Church. We need, in short, to get our bearings.

Last summer opened with revelations regarding Theodore Edgar McCarrick, who rose through the ranks to become Archbishop of Washington, DC – the capital see of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful nation – and a cardinal. Rumours of his debaucheries swirled for years. He knew the right sort of people, though, inside and outside the Church hierarchy. He also knew how to get the right sort of people to cut a cheque.

With rare exceptions, the bishops of the United States continue to protest ignorance of McCarrick’s perverse character and proclivities. Those protestations are, in a word, incredible. It may be that few had direct, personal knowledge of his abuse of minors, but it is almost impossible to avoid the conclusion that anyone who had not heard of his predilection for young priests and seminarians was either utterly benighted or living in a hermitage. The impression is that McCarrick’s habits were widely whispered, and of little concern.

They were not the stuff about which to make any sort of fuss.

The Vatican’s promises to review the documents on file relating to McCarrick and report any findings “in due course” are so woefully inadequate as to be insulting to the faithful in the US and abroad. Those promises, too, are incredible.

Had the powers in Rome dealt with McCarrick expeditiously, Pope St John Paul II would never have installed him at St Matthew’s Cathedral in 2001. There are too many reputations at stake. Too many of the men with power to influence the results of any such investigation have too much to lose through genuine transparency.

If further indication were required to show that the circumstances have grown intolerable, then consider that McCarrick and Bishop Bransfield were both major players in the Papal Foundation, which was launched in 1988 as a fundraiser for the Holy See.

The Vatican was cash-strapped after the implosion of the Banco Ambrosiano in 1982. But the Holy See eventually got its books balanced, and the Papal Foundation became a support engine for certain charitable initiatives which both the popes and the foundation deemed worthy.

The Papal Foundation, which at last count controls assets of more than $200 million (£157 million), has been embroiled in scandal for more than a year now, ever since news broke of a donor uprising over a very unusual and – it is alleged – highly irregular approval of a plan to bail out a struggling and scandal-plagued hospital in Rome.

Only a thorough and complete investigation can hope to reveal a detailed picture of all that has gone wrong. Nevertheless, the facts before the public are already sufficient to warrant systematic scrutiny.

What McCarrick did with the prodigious monies he raised, as well as the extent to which his fundraising proficiency affected the judgment of those in a position to do something about him, are both the sort of things an investigation with a broad mandate would want to discover. They also – indeed, primarily – pose a question for the faithful, in whose trust the bishops have held and managed the temporal goods of the Church, for centuries now increasingly without any meaningful check or oversight worth the name.

Let us not mince words about this: if “Pray, pay and obey” has been the maxim by which the bishops have governed the flock, the willingness of the laity to suffer their misrule can no longer be taken as patience; rather it must make us all complicit in their contempt for law, decency and common sense.

In late August last year, I argued in these pages that reform of the warped clerical culture bent to the preservation of corrupt power was urgently necessary. “The motor of the clerical culture we have right now,” I argued, “is the intrinsically perverse libido dominandi (will to power), rather than a perversion of the libido coeundi (sex drive).” The root of the problem is power.

The crucial challenge here and now is to see that money is at once a means to power and a measure of it, as well as a principal tool of its exercise.

“Power tends to corrupt,” Lord Acton famously said, “and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” He was discussing the papacy when he said it, and specifically the temporal power that had accrued to it. He was referring, moreover, at once to the effect of power on the soul that wields it and to the modes by which the one who holds power works it on others.

The creation of pecuniary dependency is a chief instrument of the powerful, sometimes deployed tactically and at other times strategically. Often we have heard how clerics of the lower ranks depend on the Church – in the case of secular priests, on the bishop – for their livelihood. Fearful of losing it, they keep silent and suffer, or else become unwillingly parts of the system in the hope of escape from their difficult circumstances, if not willing seekers after advancement.

Taken singly, or even in pairs or groups of three, the numerous examples of such silence one could list might all be chalked up to coincidence, the unremarkable vicissitudes of a complex global organisation. But under the current circumstances, any overseer worth his salt would want to take a closer look.

The laity, meanwhile, demand real reform, genuine renewal and the exercise of their right to responsible participation in the project.

Veteran Church-watchers John Allen and JD Flynn have written insightfully, noting that much disagreement over what to do hinges on the question whether the great object is management, or resolution; and that reform and renewal are objects in tension with one another. We cannot escape the world. Power will be with us, hence money, hence all the dangers that shall accompany both, so long as we find ourselves this side of celestial Jerusalem. In this sense, the problems facing the Church require reform – management – rather than resolution.

The great task before us is therefore twofold. We must clear the sacristies and chanceries and rectories of filth. Then we must discover a way to police them that involves all members of the body, without violating the hierarchical constitution of the Church, which is of divine origin.

All that work will require renewal – conversion – which is always the work of the Spirit in us.

Christopher Altieri is a Rome-based contributing editor of the Catholic Herald