The Catechism: 25 years old this month (CNS)

The approach of the Council could not be persuasive if it was not also complemented by definitive teaching

By Fr Raymond de Souza, Catholic Herald, Oct. 28, 2017

Many of the observances of the 25th anniversary of the Catechism of the Catholic Church noted that it was the most important magisterial act of the Church since the Second Vatican Council. That’s true, and it remains the towering achievement of the historic 35-year pontificate in two acts of Pope St John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Yet the Catechism was important not only for what it taught, but how it taught. It was the needed complement, or completion, of the magisterial gambit of Vatican II.

When Pope John XXIII summoned the Council, he proposed an innovation – a “pastoral council” that would not resolve any specific doctrinal points, but rather propose afresh the same deposit of the faith. He insisted that the doctrine of the faith would not change, but that it should presented in methods more adapted to new circumstances. Anathema sit was out; the “medicine of mercy” was in.

Looking back at distance of more than a half-century, the afflatus that moved St John XXIII is easy to see. A radically individualistic age, prizing a freedom of autonomy above all else, was not likely to be effectively evangelised by declarations given by authority. So John XXIII indicated a different path, a Council that would propose, not condemn, invite not exclude.

That approach met the cultural upheaval of the 1960s. The Council decision not to provide a clear, definitive interpretation of its own teaching rendered the magisterium a source of ambiguity and confusion, despite the theological richness of the Council’s teaching itself. The problem was immediately seen by the “great helmsman” of Vatican II, Pope Paul VI. He saw that the approach of the Council, as attractive as it was, could not be persuasive if it was not also complemented by the clarity of definitive teaching about what was – and was not – compatible with Christian discipleship. And he tried to do something about it.

In June 1968, at the conclusion of a “year of faith” called to commemorate the 19th centenary of the martyrdoms of Peter and Paul, Paul VI proclaimed his “Credo of the People of God”, an astonishing document in which the Holy Father begs the Church to retain the orthodox faith. Ten years later, in his last major address just weeks before his death, Paul VI would insist that he had “kept the faith”. It was “above all” the Credo of 1968 that he had in mind.

As he explained in June 1968:

In making this profession, we are aware of the disquiet which agitates certain modern quarters with regard to the faith. They do not escape the influence of a world being profoundly changed, in which so many certainties are being disputed or discussed.

We see even Catholics allowing themselves to be seized by a kind of passion for change and novelty. The Church, most assuredly, has always the duty to carry on the effort to study more deeply and to present, in a manner ever better adapted to successive generations, the unfathomable mysteries of God, rich for all in fruits of salvation. But at the same time the greatest care must be taken, while fulfilling the indispensable duty of research, to do no injury to the teachings of Christian doctrine. For that would be to give rise, as is unfortunately seen in these days, to disturbance and perplexity in many faithful souls.

Disturbance came in abundance and the beauty of the faith, so desired by John XXIII to shine with greater brilliance, seemed obscured.

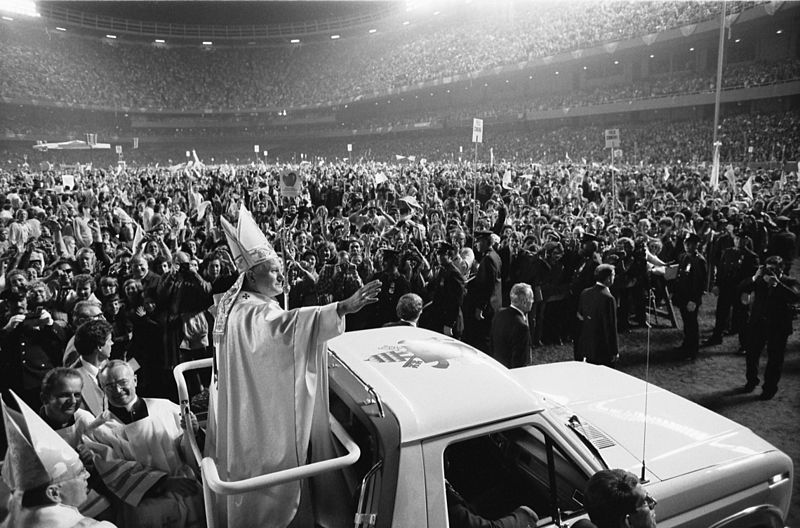

It was to address that problem that Pope John Paul II called the extraordinary synod of 1985, precisely to address what had gone wrong after the Council. As Cardinal Francis Arinze of Nigeria put it in his pithy, witty style: “How can [anyone] join a group of permanently confused people who don’t know where they’re going?”

It was the 1985 synod that called for a universal catechism, a project that John Paul entrusted to Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who in turn shepherded it to a successful conclusion 25 years ago.

To make the point, John Paul promulgated it precisely on October 11, 1992, 30 years to the day after John XXIII opened the Council by outlining his pastoral approach. (October 11 is now St John XXIII’s feast day.)

The Council’s approach, in the intervening 30 years, had not been found incorrect, but incomplete.

The Catechism did not adopt the traditional question-and-answer format, nor did it enumerate condemned propositions. It employed the positive, persuasive proposal of the faith which Vatican II envisioned, but added the specificity and clarity that the Council lacked. It was now possible to easily know that the Church taught this, and not that. Like the rest of John Paul’s massive output, it was deeply biblical – another hallmark of Vatican II – and followed the outline of the ancient catechisms, though in a fully contemporary style.

The Catechism provided the necessary centripetal force – a centre of gravity – required by a centrifugal cultural moment. The immensity of the project reflected the conviction of John Paul and Ratzinger that the magisterium, though needing to adapt and develop, was too vital to be diminished by ambiguity or confusion. They accomplished what Paul VI knew needed to be done. In doing so, they saved the Council’s teaching from the difficulties of its own cultural moment.

Fr Raymond J de Souza is a priest of the Archdiocese of Kingston, Ontario, and editor-in-chief of convivium.ca

This article first appeared in the October 27 2017 issue of the Catholic Herald. To read the magazine in full, from anywhere in the world, gohere