Why the uproar from some Catholic pundits regarding the recently released essay on the abuse crisis from Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI?

I think it’s pretty simple—regardless of what else one thinks of Benedict (and most of the critics were never fans of his), he speaks and write with a voice that is truly paternal. The man has fully lived out his priesthood as “Father” and even in his nineties, he has a father’s care for the faithful. Benedict’s voice is a unique mix of theological clarity, precision, and paternal affection.

Many would rather ridicule and criticize his words instead of accepting them as they would from a loving father. But it’s precisely because of his unique voice that the critics are hard-pressed to dismiss him. Let’s take a brief look at his essay on the abuse crisis, originally published in German for a modest monthly Bavarian publication called “Klerusblatt” and addressed largely to fellow German clergy.

But first we need to keep in mind that Benedict is addressing these German clerics from his own lived experience and memory. Benedict will conclude his essay focusing on a truly “interior” landscape that can provide a basis for a more practical nuts-and-bolts response of the Church to the abuse scandal.

In short, he’s a German theologian primarily looking at the issue as a theologian of his age and experience would be expected to do.

He lays out his thoughts in three major sections: he presents the “wider social context” of the scandal that is crucial to understanding it; he then examines the effects of this context on priestly formation and life; and then he presents some “perspectives for a proper response” to the issue by the Church.

In the first part, Benedict gives us a glimpse of how he personally encountered this context in concrete times and places as a member of the German clergy. Likely, given his audience, he presumes this will be of interest to his countrymen and brother priests.

So, while some have objected to some of his comments as seemingly out of place, in context they do make real sense—they are literally a part of his past, not just mere anecdote or speculation. We need to keep in mind that when Benedict talks about the “Sexual Revolution” he lived through that revolution in Europe, not the United States. In his country, it took shape as aggressive sex education took hold in German schools. He references another example of an Austrian sex-ed “suitcase” of resources that was prevalent in the late 1980s; he notes the influence of sex and porn films shown openly in German cinemas. He refers to a 1970 German billboard featuring a fully naked couple embracing.

For Benedict, the sexual license that overwhelmed culture arose largely from that 1968-era “revolution” that we in the United States definitely know all too well. But then Benedict references something that I for one had not properly considered or understood about this period of social upheaval. He mentions that the “physiognomy” of this era included the serious push to normalize and legalize pedophilia itself.

Readers, take note of that. It’s an important reminder that sex “experts” of the day sometimes did not stop at recommending the normalization of homosexuality and fornication as “healthy” human experiences, but that even pedophilia itself was being touted in similar fashion by some unapologetic voices of that time.

Then Benedict focuses on his experience as a theologian living through the absolute undoing of moral theology that took place in the same era. The move was from natural law and its moral absolutes to moral relativism and the “proportionalism” that became the darling of Catholic clergy and moral theologians of the 1960s and beyond. This compelled Pope John Paul II to defend the Church’s truth in his encyclical “Veritatis Splendor.” Moral theologians in Benedict’s sphere were determined to reject the existence of any absolute moral evil, and this further eroded the sense of morality among Catholics in general and even clergy in particular.

Benedict notes the perennial value of martyrdom and witness to the absolutes of both faith and morals. He lived through the attempt to weaken the role of the Church’s Magisterium as the final arbiter of such matters. In the face of this weakening Benedict calls us back to faith in God and to an awareness of our existence as “image of God.”

In the second part, Benedict illustrates how 1960s radicalism affected the priesthood and seminary formation. Tradition and traditional morality and theology all were readily jettisoned in seminaries that featured “homosexual cliques” which had a major impact on these environments. “Pedophilia” (a word which Benedict appears to use here as a catch-all for clergy sex abuse) arose as an issue of concern in the 1980s, which posed a problem as the newly constructed 1983 Code of Canon Law had not made an adequate provision for addressing such matters.

Benedict notes that Church justice emphasized “guarantorism,” in which the rights of the accused, not the victim or not even the good of the Faith itself, is held as the principal value. He suggests that canon law needs to provide a “double guarantee” that includes “legal protection of the good at stake.”

In the third part, he asserts that the experiment of coming up with a “new” kind of Church to solve these problems has actually been tried and failed. The real answer is only found in the Church founded by Christ, not re-made by us.

The landscape for a true solution will necessarily mean that we need a culture and society that includes God. “Absence of God” is what Benedict says ultimately brings about a society that begins to excuse even pedophilia. Clergy and laity often don’t like to speak about God.

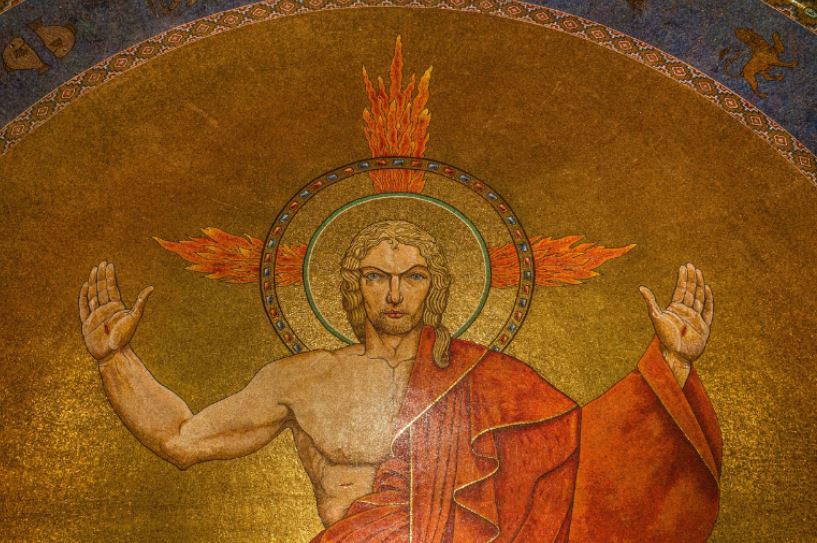

In doing so, we must again re-centralize the Eucharist in the Church. Benedict says: “What is required first and foremost is the renewal of the Faith in the Reality of Jesus Christ given to us in the Blessed Sacrament.”

Lastly, Benedict states we must rediscover the “Mystery of the Church” and once again profess to live as its “martyrs”—as real witnesses. To do so means that whatever sin and evil remain in our midst can not prevail over the “indestructible” Church founded by Jesus Christ, the “first and actual witness for God” and the first martyr.

Benedict’s message is clearly not intended as a magic-bullet solution for the abuse crisis. For others to criticize it for merely being what it really is—a loving word of encouragement from a spiritual father—is to miss the boat entirely on his intention and on the true value of what he has written. Even at his advanced age—or perhaps precisely because of it—his words provide a kind of consolation and encouragement that fathers are especially good at in challenging times. All is not lost. He knows we’ve been through a lot because he himself lived through it. But there is a way forward.

And some fundamental words of wisdom from a spiritual father who still loves us—remember God, and love Jesus in the Eucharist—could help us all heal a little bit faster.