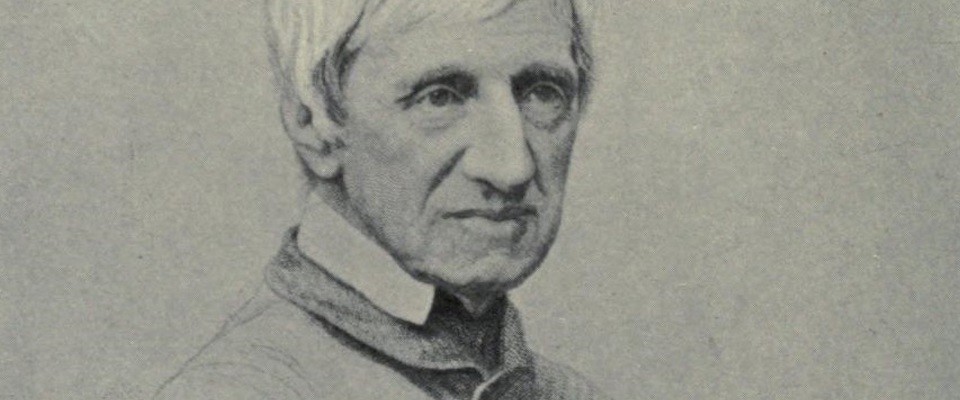

Aspectre is haunting the preparations for next month’s Amazon Synod: the spectre of John Henry Newman, who will be declared a saint on October 13, a week into the synod’s proceedings. The canonization of this towering figure—a model priest, the founder of the English Oratory, and a literary and theological genius—is above all a moment for rejoicing. But it’s only fitting to have a little controversy around the occasion too. “I am a controversialist,” Newman used to insist, “not a theologian.” Just as his writings were often prompted by the conflicts of his time, so they illuminate the Church’s present confusions.

For instance, one common criticism of the Amazon Synod’s working document is that it blurs the distinction between Catholicism and pagan nature-worship. The document is too clumsily-written to directly challenge Church doctrine, but its ambiguities seem to allow the possibility that paying homage to Mother Earth is practically as good as worshipping the Holy Trinity. “Indigenous rituals and ceremonies,” the document enthuses, “create harmony and balance between human beings and the cosmos.” Its words about the Mass, by contrast, are perfunctory. While the document tells us that “Jesus offers life to the full,” it’s quickly clarified that this “life” means things like “abundant bio-diversity.” Those who vaguely remember that the Catholic Church is supposed to be the one ark of salvation will be put in their place by the document’s chilly rejection of “a corporatist attitude, that reserves salvation exclusively for one’s own creed.”

Now, if it’s “corporatist” to believe that only one creed saves, then Newman was his age’s leading exponent of corporatism. He urged his Anglican friends, for example, to join “that faith and that Church in which alone is salvation.” Newman realized that this point had to be nuanced, but he never let the nuance hide the basic imperative. “Whenever conviction comes to you,” he wrote to one spiritual seeker, “that the Church of Rome is the Church, you ought to act upon it at once.” In his late seventies, he reflected that he had spent his life in hand-to-hand combat with “liberalism.” What did he mean by liberalism? “The doctrine…that one creed is as good as another.” Compare this plain speaking with the Amazon Synod’s blurred lines.

Thus Newman, while endlessly kind toward his opponents, nevertheless shuddered at any hint of heresy. After making peace with Orestes Brownson (who had once fiercely attacked him in print), Newman wrote to Brownson that Catholics should, in general, interpret one another’s words as charitably as possible and do everything to preserve Church unity. There was one exception: “If we have traitors among us, of course let them be duly dealt with.” If “treason” was “suspected,” Newman argued—if someone was not merely mistaken, but was actively undermining the foundations of the faith—then the normal rules of generous and open discussion did not apply.

Newman’s distinction helps to explain the widespread alarm about the Amazon Synod. One of the synod’s goals, it appears, is to smooth the path toward married priests and/or some kind of “increased role for women.” Both are theologically complex questions—but Catholics are entitled to put aside that complexity and simply raise their voices in protest when they see the men who are in charge of the event. When you consider that the cardinal presiding over the synod, Claudio Hummes, has said he doesn’t know if Jesus would have supported same-sex marriage; that the bishop leading the way in the pre-synodal discussions, Erwin Kräutler, is an advocate for women priests; and that Leonardo Boff, arguably the intellectual godfather of the whole thing, was censured by John Paul II for “endanger[ing] the sound doctrine of the faith,” you have to wonder what this synod is really about. It claims to be addressing the exploitation of the Amazon. But to pretend to address that appalling reality, while actually using the occasion to adulterate Catholic doctrines and disciplines, would itself be a kind of exploitation.

If most bishops are keeping quiet about the synod, it is partly because of a widespread feeling that Catholics mustn’t raise doubts over anything linked with Pope Francis. That is, in a way, a laudable impulse; Newman certainly felt it, writing in 1866 that we should defend the pope “as a wife a husband, knowing that his cause is the cause of God.” But over the next few years Newman’s emphasis changed, as his letters show. He saw Pius IX’s rule spreading doctrinal confusion and spiritual distress among Catholics, made worse by a “violent ultra party” which exaggerated papal authority as part of an attempt “to destroy every school of thought but its own.” As this party advanced, “It seems to me a duty, out of devotion to the Pope and charity to the souls of men, to resist it, while resistance is possible.”

After all, Newman reasoned, there had been popes like Liberius and Honorius who fostered disastrous doctrinal errors, if only by ambiguity. In 1870, the Vatican Council taught that popes were infallible when speaking ex cathedra; but Newman observed that the vast majority of things popes said were not ex cathedra (to use a theologian’s term, they were extra cathedram); therefore, Catholics were not obliged to welcome everything the pope did or said. As he put it in an 1872 letter to Bishop David Moriarty:

I am not saying a word against the dogmatic authority of the doctrine of papal infallibility—but, if popes cannot teach falsehood ex cathedra, they can extra cathedram do great evil, and have done so before now. I suppose Liberius and Honorius are instances in point. If they, why not Pius?