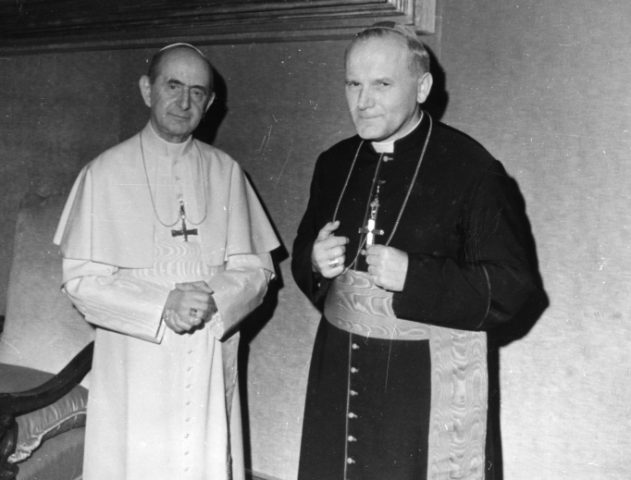

Photo: Pope Paul VI (l) greets his future successor, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, at the Vatican. Pope Paul and St. John Paul II were the leading moral voices on human sexuality and marriage in the last half of the 20th century.

By Matthew E. Bunson, National Catholic Register, 7/24/18

The year 1968 remains a watershed moment in an era of revolution and upheaval.

With the world engulfed in social, political and especially sexual upheaval, the year witnessed the brutal rejection of a relatively brief papal document that sought to clarify the Church’s teachings on family life and the regulation of births. Humanae Vitae (The Regulation of Birth) remains one of the most polarizing papal encyclicals of all time, but also one of the most prophetic in foreseeing vividly the immense dangers of a contraceptive culture that ultimately came to pass.

The origins of Humanae Vitae, however, are also an important part of Church history, because the commission that preceded it — especially the commission’s final report — also anticipated and even embodied the dissent not just from teachings on human sexuality, but from the whole of Church authority.

It is also a story of how Pope Paul VI remained faithful to the Petrine Office in the midst of a cataclysm and how a small group of theologians stood firm against the winds of dissent and dishonesty.

The Problem of Contraception

It was a strange twist of history that so much damage would be done to the moral credibility and authority of the Church’s teachings by something that had been unanimously condemned for the entire history of Christianity.

Both Scripture and Tradition unceasingly rejected contraception, defined as “any action which, either in anticipation of the conjugal act [sexual intercourse], or in its accomplishment, or in the development of its natural consequences, proposes, whether as an end or as a means, to render procreation impossible” (Humanae Vitae, 14).

So clear and unequivocal was the teaching that contraception is intrinsically evil, contrary to the natural law and a threat to marriage and family life that even the Protestant Reformers remained faithful to the prohibition, and every Christian denomination was firm in its rejection of contraception until the 20th century.

As late as 1908, the bishops of the Anglican Communion gathered at their Lambeth Conference and reiterated that artificial birth control is “demoralizing to character and hostile to national welfare.”

This began to change, however, as the resolve of the Christian denominations began to fade.

By the 1930 Lambeth Conference, the Anglican bishops took the absolutely unprecedented step of allowing birth control, under what they called the guidance of “Christian principles.” Even then, however, the Anglicans understood that contraceptives would incentivize casual sex and so pathetically urged that their sale be restricted. By the late 1950s, the Anglicans were encouraging birth control for all, and today the Episcopal Church in the United States supports abortion.

Alarmed by what had happened at Lambeth, at the end of 1930, Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Casti Connubii (Christian Marriage) that condemned contraception anew as an existential threat to family life and marriage:

“Any use whatsoever of matrimony,” Pius wrote, “exercised in such a way that the act is deliberately frustrated in its natural power to generate life is an offense against the law of God and of nature, and those who indulge in such are branded with the guilt of a grave sin” (56).

Over the next decades, however, new forms of contraception were being developed. In May 1960, the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of Enovid, a hormonal contraceptive pill that was hailed as revolutionary in its supposed ability to regulate fertility with no significant side effects.

The Papal Commission

Pope St. John XXIII initially expected the question of birth control to be addressed by the Second Vatican Council that he had opened in 1962. The Pope, however, was convinced by his advisers, especially the Belgian Archbishop (later Cardinal) Leo Joseph Suenens, that given the complexity of the issues, the Council was not the most ideal setting and that a separate commission would be better suited to study the Church’s response, especially as birth control was being embraced by the United Nations and the World Health Organization for developing countries.

On April 27, 1963, barely a month before his death, John created the Pontifical Commission on Population, Family and Birth Rate. Dominican Father Henri de Riedmatten, an official of the Vatican Secretariat of State, was named the commission’s secretary-general. He proved the most pivotal figure in the subsequent and tortured history of the commission. Pope John died June 3, 1963, and Cardinal Giovanni Montini was elected pope 18 days later and took the name Paul. The new pope thus inherited the commission and concurred that it should continue, but he also agreed to expand its membership.

What had begun as a modest commission of six members, including two medical doctors, soon grew from 1964 with the addition of cardinals, bishops, theologians, scientists, physicians, sociologists, laypeople and a married couple. Forty-three new members were added in 1965, and by the end of its work the next year, it had more than 70 members.

While the mandate of the commission was never clearly defined, Pope Paul was not wavering in the Church’s teachings on contraception. But he was apparently willing to study the highly technical question of whether the pill was still contraception and wanted to hear arguments from both sides.

The famed moral theologian Germain Grisez, who died Feb. 1, worked closely with one of the commission members, Jesuit Father John Ford. Grisez wrote that Paul “believed that a thorough study was needed to ensure that the Church would not ask more of faithful Catholic married couples than God did.” Equally, it was never his intention to call into question received teaching, most recently in Casti Connubii, the commission was not to have any formal authority, and he expected its proceedings to be confidential. At the end, there would be a report sent to him alone.

None of that happened.

A Predetermined Conclusion

From the very beginning of its existence, the commission moved well beyond the question of the pill and into the theological debate of whether Casti Connubii and the magisterial teachings of the Church on contraception were reformable. In other words, can the unchanging teachings of the Church actually be changed?

Under the guidance of Father de Riedmatten, the commission headed in a direction that was fixed to allow for a change to Church teaching. In the end, when a vote was taken June 20, 1966, the final report calling for the acceptance of contraception received approval from nine of the 15 prelate members who were present, 12 of the 19 theological authorities and virtually all of the carefully chosen lay members.

Among the prelates who supported the change were four cardinals, including Suenens, Julius Döpfner of Munich and Lawrence Shehan of Baltimore. Archbishop Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, Poland, the future Pope John Paul II, was prevented from attending by the communist authorities in Poland. He was known to be opposed to any change in Church teaching, and his absence was felt keenly by the small group of theologians on the commission, including Father Ford, fighting against the tide of dissent.

The final report was presented to Pope Paul by Father de Riedmatten June 27, 1966, and concluded with the “Draft of a Document Concerning Responsible Parenthood,” a synthesis of the majority opinion for changing Church teaching. Father de Riedmatten added it to the very end as a kind of capstone to the effort to sway the Pope.

In the appendices were two other notable documents. The first was “Synthetic Document Concerning the Morality of Birth Regulation” that was effectively a rebuttal to what followed, “The Status of the Question, the Teaching of the Church, and Its Authority,” that was written by Father Ford and Grisez and signed by several other theologians as a reaffirmation of Church teaching that contraception is intrinsically evil and an outlining of the potential damage that might follow if the teaching were repudiated.

Pope Paul’s Response

By the time the commission had finished its work, there was a growing expectation on the part of many dissenting theologians that it was only a matter of time before the Pope declared that contraception was now permitted by the Church.

The Holy Father’s address Oct. 29, 1966, to a gathering of Italian obstetricians and gynecologists thus came as a surprise. He told the physicians that the commission “cannot be considered definitive, owing to the fact that they present grave implications with other not few and not slight issues, doctrinal, pastoral and social, which cannot be isolated and set aside. … This fact indicates, once again, the enormous complexity and tremendous gravity of the subject relating to the regulation of births and imposes on us the responsibility of supplemental study.”

In the spring of 1967, leaked translations of several of the commission documents were published in French and English, including by the National Catholic Reporter and The Tablet. This was part of an orchestrated campaign by proponents of changing Church teaching to pressure Pope Paul and to heighten further expectations of an imminent revolution. The draft document was published as the “majority report,” while the document by the theologians faithful to the magisterium was dubbed dismissively as the “minority report.”

The leaks caused a firestorm in the media, and the majority report was treated as a magisterial pronouncement.

At last, July 25, 1968, Paul acted in accord with what he had planned all along. He had listened to the arguments of both sides on the commission and replied with Humanae Vitae, “On Human Life.”

Paul thanked the commission for its work, but he addressed its severe problems.

“The conclusions arrived at by the commission,” he wrote, “could not be considered by us as definitive and absolutely certain, dispensing us from the duty of examining personally this serious question. This was all the more necessary because, within the commission itself, there was not complete agreement concerning the moral norms to be proposed, and especially because certain approaches and criteria for a solution to this question had emerged which were at variance with the moral doctrine on marriage constantly taught by the magisterium of the Church” (Humanae Vitae, 6).

The Pope courageously embraced the minority view of the commission and issued a relatively brief but clear vision for family life and the Church’s opposition to contraception. Humanae Vitae, however, did not provide what he had hoped: a definitive ending to the discussion of contraception and a clear vision for Catholic bishops, teachers and the faithful.

Instead, great damage was done by the unconscionable leaks and the media storm against Paul’s refusal to abandon his duty as Supreme Pontiff.

Fifty years on, the world sees poignantly that Pope Paul was a prophet about the impact of contraception, but the minority members of the commission also proved prophetic.

Just as they feared and predicted, the rejection of the encyclical meant, also, that many theologians declared themselves — and the Catholic faithful — free not just from the moral teachings of the Church, but from the magisterium itself.

They, and not Pope Paul or the encyclical, are to blame for that.

Register senior editor.