This is the second in a series of four postings on African American Spirituals.

In this second article on the Spirituals lets review of some of the general history of the Spirituals and then, we look to the theme of HOPE.

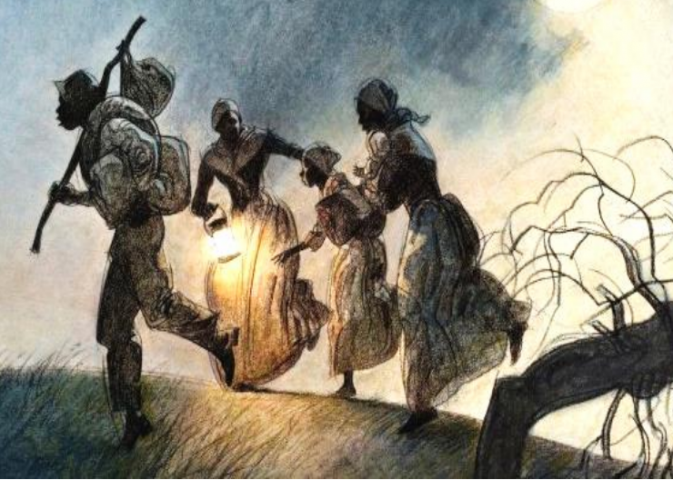

The Spirituals of the African-American tradition, sometimes called the “Negro spirituals” are songs created by enslaved Africans in the decades prior to the Civil War. They do not have individual composers, but emerged from the whole community. They were passed orally from person to person and improvised as suited the singers. They were crafted in the fields where the slaves would sing to pass the day and ease the often tedious work of planting, tending and harvesting the crops. Some were simple work songs that were sung in a call and response style. Over the years, the slaves and their descendants adopted Christianity, the religion of their masters, and they began to include religious themes into their field songs. They re-shaped it into a deeply personal way of dealing with the oppression of their enslavement. These songs, became known as spirituals and reflected the slaves’ expression of their faith. The songs told stories, from Genesis to Revelation: Adam and Eve in the Garden, Moses and the Red Sea. They sang of the battle of Jericho, Ezekiel seeing a wheel, Mary, Jesus, the blind man seeing, God troubling the water, and yes, the Devil, as one to avoid!

Some of the best known spirituals include: “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” “Nobody Knows The Trouble I’ve Seen”, “Steal Away,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Go Down, Moses,” “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hand,” “Every Time I Feel the Spirit,” “Let Us Break Bread Together on Our Knees,” and “Wade in the Water.”

The Spirituals have great authority since they were written in the cauldron of great suffering. If any people might be excused from thinking that the Lord had forsaken them or, that they would be exempt from judgment day, it was surely the enslaved in the Deep South. If any people might be excused from crying out for vengeance, it was those enslaved in the South. And yet the spirituals are almost wholly devoid of condemning language. Enslaved blacks sang in ways that looked also to their own sins and need to be prepared. If they were prepared, God, who knew their trouble, would help them to steal away to Jesus. They did not see themselves as exempt from the need to be ready and to persevere in the faith. In the years following Slavery, these songs were collected and given choral form that included elaborate harmonies and swift rhythms. The spirituals are wonderfully creative and contain a wisdom that comes from suffering and a hope that comes from faith in God’s promises. The African American Spirituals are a national treasure and gift to the Church of immeasurable value.

Now we turn to the theme of Hope.

There is an old story told of a young slave girl who lamented to her mom, “Mama, all the White folks got shoes, why don’t we?” Her mother replied, “Oh, we got shoes alright. See,

I got shoes, you got shoes, and all God’s children got shoes! When we get to heaven gonna put on our shoes and go walk all over God’s heaven.

And then Mama said “Remember child,” Everybody talkin’ ‘bout heaven ain’t a goin’ there.”

(NOTE: Click on the songs in blue text for links to the internet to hear versions of these Spirituals).

So, songs and sayings like these got taken into the field by the slaves and became the foundation of the Spirituals. In the midst of great injustice and oppression with no end in sight, one can become depressed and angry. The message of the Spirituals drew on biblical stories and themes of life to convey the hope of ultimate victory in Jesus and the reward for faith. They were a kind of “Balm in Gilead to heal the wounded soul.” The oppressed looked beyond this valley of tears to heaven where joys unspeakable and glories untold awaited the faithful Christian. One spiritual says,

“I am a poor pilgrim of sorrow, I’m tossed in this wide world alone. No hope I have for tomorrow, but I’ve started to make heaven my home. Yes, sometimes I am tossed and driven, Lord, Sometimes I don’t know where to roam. But I’ve heard of a city called heaven and I’ve started to make it my home.”

Another spiritual asked God to hold them tight, they sang:

“Rocka my soul in the bosom of Abraham, Oh, rocka my soul!”

Yet, another spiritual reminded the slaves of God’s deliverance in previous days:

“Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel? Then why not every man?”

Meanwhile, as another spiritual exhorts:

“Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me round, marchin’ up to freedom land.”

That’s because

“I promised the Lord that I would hold out, until my change comes! Yes, He said he’d meet me in Galilee.”

Meanwhile we’d better:

“Walk together Children, there’s a great camp meeting in the Promised Land!”

These songs gave hope in the midst of great sorrow and oppressive slavery. And this hope was not only in heaven after death, it was now as well. Many of the songs had double meanings. The city called heaven that I am “trying to make my home” was also code for the North where freedom could be found. “Marchin’ up to freedom land” could mean heaven but it could also mean the land of freedom up north. The slaves knew that not every blessing had to wait for heaven. God is in the blessing business right now. The spirituals sought to give courage to fellow slaves to forsake fear and look for opportunities to lay hold of their God-given freedom.

Continue reading >>>>