By Michael Pakaluk, The Catholic Thing, June 12, 2018

Nothing shows better how Christianity affects human consciousness than how I think about suicide – taking myself as a random member of Christendom – but likely you too.

From childhood, I have recoiled from it. How could I dare take my own life? I lack the authority to do so. Others have given so much: all those hours, sacrifices, and money, expended on clothing, feeding, safeguarding, and educating me. I represent an enormous investment by many others.

To take my own life, after all that effort, would be as pointless as my serving as cannon fodder in some meaningless war. In any case, suicide couldn’t but be, as an act, something that was highly magnified solely in my imagination, while being next to nothing in reality.

“How did we fail to hear his cry for help?” someone might say the next day – but a day or two more, and it would be forgotten. No one would learn a lesson from it, that’s clear. “I’ll show them!” – No, I won’t.

And yet, what I just rehearsed in that last paragraph – an exercise in pure “reason,” it seems, with no appeal to “revelation” – has demonstrably come easily only to those in Christian civilization. “The advent of institutional Christianity was perhaps the most important event in the philosophical history of suicide, for Christian doctrine has by and large held that suicide is morally wrong, despite the absence of clear Scriptural guidance regarding suicide,” as the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (rather clumsily) puts it. Christians take the fact as a badge of honor, but secularists use it to impugn the rationality of our view.

So do we say that our reasoning is specifically Christian, or that Christianity has merely strengthened what belongs to human reason on its own? How could we tell?

Allow a couple of centuries for this conviction to continue to strengthen. Add the premise, so clearly articulated by St. Thomas, that the criminal law rightly proscribes actions which are inherently wrong and serious (while prescribing the inherently good ones, and permitting the indifferent ones), and one arrives at the position of Blackstone’s Commentaries, that “self-murder” is a felonious crime:

the law of England wisely and religiously considers, that no man has a power to destroy life, but by commission from God, the author of it: and, as the suicide is guilty of a double offense; one spiritual, in invading the prerogative of the Almighty, and rushing into his immediate presence uncalled for; the other temporal, against the king, who has an interest in the preservation of all his subjects; the law has therefore ranked this among the highest, crimes, making it a peculiar species of felony, a felony committed on oneself. A felo de se [“felon of himself”] therefore is he that deliberately puts an end to his own existence.

Harmony is a sign of truth. Blackstone’s reasoning tracks not merely our own but also that of countless authorities, such as St. Thomas in the Summa– not because of anyone’s rote imitation of anyone else, but because of a coincidence in rational judgments.

St. Thomas adds this interesting argument. In response to the objection that suicide is not self-murder, because no one can do an injustice against himself, St. Thomas says, “Murder is a sin, not only because it is contrary to justice, but also because it is opposed to charity which a man should have towards himself: in this respect suicide is a sin in relation to oneself.”

Note the presupposition that the wrongness of murder consists perhaps primarily in the evil done to oneself – after all, it is an act by which someone makes himself into a murderer! The wrong of suicide is located not simply in what is taken away (from God and society) but also in the taking.

Suicide and attempted suicide remained crimes until recently in Australia (1958), Britain (1961), and Canada (1972). In the United States, most States held likewise through the 1960s. In February 2018, a man was convicted of the felonious crime of attempted suicide in Maryland – legal recourse deemed necessary to make it easier to take away this unstable person’s weapons.

Punishments for suicide can look harsh, because what can one do except attack the estate of the deceased, or (as in English law, formerly), bury the body at the crossroads instead of in hallowed ground? Suicide laws were decriminalized, no doubt, in part as a reaction against this perceived harshness. But there were two other causes.

One was the triumph of a line of thought already scouted by Blackstone, namely, that “the very act of suicide is an evidence of insanity; as if every man who acts contrary to reason, had no reason at all.”

Blackstone replies, “the same argument would prove every other criminal non compos [of unsound mind], as well as the self-murderer. The law very rationally judges, that every melancholy or hypochondriac fit does not deprive a man of the capacity of discerning right from wrong.”

It seems right that the state of mind of those who attempt suicide is rarely as confused as those we excuse from responsibility for murder. Even the Catechism says only that “Grave psychological disturbances, anguish, or grave fear of hardship, suffering, or torture can diminish the responsibility of the one committing suicide.” (n. 2282)

The other cause, more ominous, was the linkage of suicide with abortion through the same misguided “political liberalism” that exalts personal autonomy – an ideology so powerful that even John Rawls and Robert Nozick came together in “The Philosopher’s Brief” (1997) to defend it. Leave it to philosophers to be perfectly clear: the right to define the meaning of the universe, so wonderfully articulated in Casey (1992), they said, if it does not include the right to suicide, neither includes the right to abortion. Suicide is the near relative of abortion.

So the question remains: how can suicide be both a sure sign of insanity, and the special object of attention by our most eminent philosophers of liberalism?

_______________________________

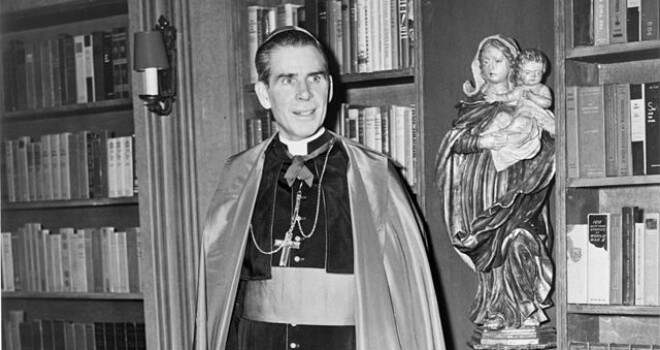

*Image: The Suicide (Le Suicidé) by Édouard Manet, c. 1880 [Foundation E.G. Bührle Collection, Zürich]