Patients’ Rights Advocate Wesley J. Smith: Human Exceptionalism Is Backbone of Civilization

Saint of the Day for June 10: Blessed Joachima (1783-1854)

June 10, 2019

Msgr. Charles Pope: The Spirit of the Lord Filled the Earth – A Homily for Pentecost

June 10, 2019

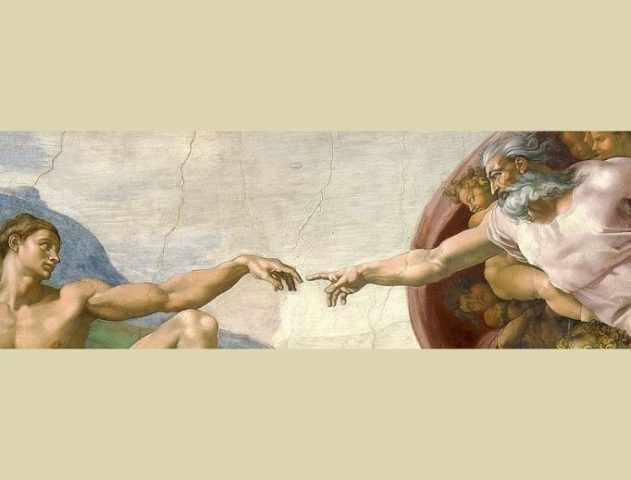

Creation of Adam, Michelangelo

An interview with the lawyer and author of several books on assisted suicide, euthanasia and the importance of human moral worth.

By Joseph O’Brien, National Catholic Register, 6/9/2019

Lawyer and patients’ rights advocate Wesley J. Smith wrote the book on opposition to assisted suicide and euthanasia. In fact, he wrote several.

And he is outspoken against such initiatives worldwide.

This week, in fact, Smith weighed in about the case of the teenage girl in the Netherlands, who suffered severe post-rape PTSD and died from starving herself after requesting euthanasia: “Does the exact cause of the girl’s death really matter? A teenager — with a terrible psychiatric condition — was allowed to make herself dead instead of receiving continued and robust treatment efforts. That’s abandonment as surely as providing a lethal injection. This is where all assisted suicide/euthanasia legalization laws eventually lead. Once a society accepts killing is an acceptable way to eliminate human suffering, there is no limit as to the categories of suffering that will eventually justify eliminating the sufferer. Those with eyes to see, let them see.”

In the U.S., on April 12, New Jersey became the latest state to legalize assisted suicide, joining Oregon, Washington, California, Vermont, Colorado, Hawaii, the District of Columbia and Montana in legalizing the brutal practice of proscribing and/or administering lethal drugs to those who wish to end their lives. Smith has been on the front lines in the battle to prevent these laws from passing around the country and has helped successfully defeat such measures in several other states.

A lawyer by trade, Smith began his career in the Los Angeles County court system, before turning to public advocacy. Today he is a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute, a conservative think tank headquartered in Seattle, which advocates for a “reinvigoration of traditional Western principles and institutions,” including a return to what Smith calls “human exceptionalism,” which holds that since human beings possess unique moral worth, the value of human life is greater than that of any other creature on earth.

Early in his career as an advocate, Smith’s two mentors were Ralph Nader, who collaborated with Smith on several books to raise consumer awareness in the legal and medical fields, and patient-rights advocate Rita Marker, who first teamed up with Smith to fight for patients’ rights — and lives — after he wrote an article for Newsweek in 1994 criticizing assisted suicide, his first foray into the politics of assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Since penning that article, Smith has written several influential works on medical ethics. Their titles alone trace the arc of his thought on these issues, beginning in 1997 with an expose of the assisted-suicide industry in Europe and America: Forced Exit: The Slippery Slope From Assisted Suicide to Legalized Murder (1997). Three years later he wrote about the shifting ground of the debate, allowing these issues to become boilerplate in secular medical ethics: Culture of Death: The Assault on Medical Ethics in America(2000). In his more recent books, Smith more directly defends human exceptionalism against the animal-rights movement (A Rat Is a Pig Is a Dog Is a Boy: The Human Cost of the Animal Rights Movement, 2009) and radical environmental activism (The War on Humans, 2014). While these last two titles may seem to have little to do with the effort to legalize assisted suicide or euthanasia, Smith argues that they represent a second front in the war against the exceptional value of human life by seeking to endow non-human and even non-living entities with the same rights that are natural to the human race, thereby negating an effective understanding of human rights altogether.

The Register spoke with Smith recently about his career in fighting the culture of death, especially as attempts to orchestrate a wholesale rejection of human exceptionalism, most visibly in the treatment of the sick and dying, is increasingly underway.

How did you develop the idea of human exceptionalism in your writings over the years?

Human exceptionalism is more than just the sanctity of human life. A lot of people wonder why I don’t just use that term. But it’s actually more than that. There are two sides of this concept that are important. First, there is the unique value of human life and the indisputable fact that there has never been another species in the known universe like human beings. The difference in us is moral not biological. For example, it isn’t our opposable thumb that gives us unique value. That’s not a moral difference; that is a biological difference.

People of faith would say human beings are made in the image and likeness of God. But I don’t bring religion into this work. Believers and atheists can agree that human beings are a truly moral species: Only we have an understanding of right versus wrong — what we ought to do. Consequently, we have obligations and duties to each other and to our posterity. That said, we also have a duty to treat animals humanely; they are not rocks or inanimate objects; they have emotions and can feel pain. We also have a duty to treat the environment in the proper way; but that isn’t the same thing as giving rights to animals or to nature.

What convinced you to undertake the work of defending human exceptionalism?

In about 2002 I was asked to speak to a high-school honors class in Canada about the importance of equal moral worth of all human beings. Afterwards, a very bright student came up to me and said, “You’re saying a human being has greater value than a bunny.” I said, “Yes.” She looked at me very earnestly and said, “No. Human beings and animals both can suffer. We’re equal.” Her response hit me like a thunderclap: The best and brightest kids we have (it was Canada but could as well have been the United States) are buying into these concepts that I thought were almost laughable. After speaking with that student, I decided I needed to focus more broadly on the question of what it means to be human. Shortly thereafter, I began to use the term “human exceptionalism.” (I’m not claiming credit for coining that term.) I thought it was important to focus more deeply on what was causing our culture to reject human exceptionalism, of which assisted suicide and the idea of taking away food and water from cognitively disabled people were only symptoms. Human exceptionalism is fundamental to everything that Western civilization stands for.

When did you first see that the rejection of human exceptionalism would lead to such consequences as assisted suicide and euthanasia?

In my first anti-euthanasia piece, called “The Whispers of Strangers,” I write about how my friend Frances killed herself. In that article, I said that if you end up allowing assisted suicide, what are the consequences going to be? Once you’ve decided that certain human beings become killable, or their suicides ought to be facilitated rather than prevented, you’ve made a profound statement about the value of that life. You’ve basically said that that life has less value than the wishes and desires of those whose suicides you would prevent or whose homicides you would impede.

How did your work opposing assisted suicide and euthanasia lead you to the Orthodox Church?

When I started the assisted-suicide work, I was not a practicing Christian. I would say I was a Christian, but I didn’t go to church. My faith did not motivate what I did, particularly. But as I was doing this anti-assisted-suicide work, for the first time in my life I could see evil as a real concept. I began to feel the evil, and I felt the need to engage my faith more fully. I was on a search for what is true. Eventually, that led to a conversion to Eastern Orthodoxy over a period of time. I became Eastern Orthodox in 2007. But my faith did not lead me to oppose assisted suicide and euthanasia; rather, these issues led me to my faith.

Why do you take a secular approach in your work with human exceptionalism and in your opposition to assisted suicide?

Back when I was a practicing lawyer, I thought that fighting assisted suicide was the liberal perspective. If you believed in protecting vulnerable people, you opposed assisted suicide. Death was not the proper response to people who were suffering or wanted to die; intervention, suicide prevention and reaching out, helping and caring for them was the proper response. In fact, I became a friend of [the late pro-life New York journalist] Nat Hentoff because of this work. Nat Hentoff was a very left-wing liberal in his views, but very much against euthanasia and assisted suicide from an explicitly atheistic perspective. If you believe in universal human equality and universal human rights, it’s the only obvious response.

It sounds like the battle to prevent legalized assisted suicide is more than a matter of right versus left, or conservative versus liberal. What’s at stake in this battle?

I think there is a contest going on right now, pitting the values of Western civilization, which comes out of a Judeo-Christian philosophy — with the help of the Greeks and Romans — against philosophical relativism. The backbone of Western civilization is the unique value of each and every individual. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” But there is another philosophy that is competing, and I think Pope Benedict XVI got to this when he spoke about the tyranny of relativism.

[Modern proponents of relativism] Peter Singer and Joseph Fletcher express this philosophy in one way or another: The point of society is to prevent suffering. That’s not the same thing at all as universal equal moral worth. If the idea is to eliminate suffering, that quickly becomes a matter of eliminating the sufferer. Soon after that, what constitutes sufficient suffering to justify the elimination of the sufferer becomes elastic. That’s why you see the expansion of categories of who becomes killable once people accept this premise.

In the United States the premise is still being tested, and so you see activists talking about terminal illness as the reason for assisted suicide and euthanasia. But that’s just a tactic; it’s not an actual belief system, because they know the way to get people to accept the premise is to limit euthanasia and assisted suicide to the terminally ill. But in societies that have now accepted the premise that killing is an acceptable answer to human suffering — such as in Belgium, the Netherlands and Canada — there’s no way it’s limited to just the terminally ill, and people will argue in these places that it shouldn’t be limited to just the terminally ill because of suffering.

How have the terms of the assisted-suicide debate shifted since you first wrote Forced Exit and Culture of Death?

Culture of Death is particularly germane. The revised edition is called Culture of Death: The Age of “Do Harm” Medicine. It came out in 2016. When the original book came out in 2000, there was only one place in the world that had legalized assisted suicide formally, and that was Oregon. After that book came out, with New Jersey, there will be a total of seven states and Washington, D.C., by legislation [and one, Montana, through a state Supreme Court ruling], the Netherlands (which had permitted it prior to this time, but formally legalized it in 2002), Belgium, Luxemburg, Columbia, Canada, Germany (assisted suicide by court order), and there’s also the growth of the “suicide tourist industry” in Switzerland.

You say that with the murder of Terri Schiavo in 2005, allowing starvation and dehydration of a patient has become settled policy in law and in medical ethics. What is the next big battle that the country is facing?

I think people need to be aware that George Soros’ money and similar forces are putting millions of dollars every year into promoting the pro-assisted-suicide agenda. The attempt to legalize assisted suicide just lost in Arkansas, New Mexico, Connecticut and Maryland, although you don’t hear about that in the secular media — only that it was successful in New Jersey. The problem is assisted suicide is permitted not as a public-policy issue; instead, it’s being turned into a right that can never be rescinded or repealed. They only won about eight states, for now, but they’re looking to get to a tipping point so they can go back to the Supreme Court.

In 1997, the United States Supreme Court ruled 9-0 against assisted suicide(I filed an amicus brief in this case that there is no constitutional right to assisted suicide.) Thanks to pro-life advocacy against Roe v. Wade and the Catholic Church’s advocacy against abortion, the court was convinced they shouldn’t make another decision like Roe v. Wade again. But I think that assisted-suicide advocates are going to come back at it, once they have 20 states, say, under their belt — arguing that it’s unequal protection for some people to have assisted suicide and not others. In this way they will try to get a constitutional right to assisted suicide. So if you lose a state here or there, you have to keep fighting to make sure they don’t reach that tipping point, which would permit assisted suicide as the law of the land.

Register correspondent Joseph O’Brien writes from Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin.