A Most Vivid Description of St. Athanasius

Priests Appeal to World’s Bishops to Address ‘Pastoral Crisis’ in the Church

May 2, 2018

Scouts’ Mixing of Genders Highlights Other Group’s ‘Boy Focus’

May 2, 2018

By Msgr. Charles Pope • May 1, 2018

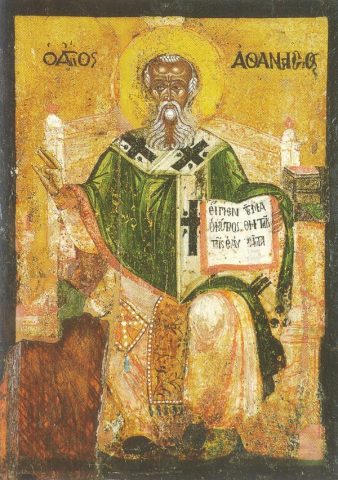

A couple of brief thoughts about St. Athanasius whose feast we celebrate today.

I have served in African-American parishes for most of my priesthood and have often wondered why there don’t seem to be any black parishes named for this North-African saint. There are many named for Augustine and Cyprian, both of whom were likely of Berber stock despite hailing from northern Africa. Athanasius, on the other hand, while certainly not a sub-Saharan African, is described as having dark — even blackish — skin. Yet almost no African-American Catholic community claims him. It just seems curious to me. I once wrote to a rather prominent historian who has written on African-American Catholicism to ask why this was so, but I never received a response.

My favorite description of Athanasius comes from The Holy Fire, by Robert Payne, whose writing style I just love. In my opinion he is at his best in describing St. Athanasius. Enjoy this vivid excerpt:

There are times when the dark, heavy syllables of his name fill us with dread. In the history of the early Church no one was ever so implacable, so urgent in his demands upon himself, or so derisive of his enemies. There was something in him of the temper of the modern dogmatic revolutionary: nothing stopped him. The Emperor Julian called him “hardly a man, only a little manikin.” Gregory Nazianzen said he was “angelic in appearance and still more angelic in mind.” In a sense both were speaking the truth.

The small, dauntless man who saved the Church from a profound heresy, staying the disease almost single handed, was as astonishing in his appearance as he was in his courage. He was so small that his enemies called him a dwarf. He had a hook nose, a small mouth, short reddish beard which turned up at the ends in the Egyptian fashion, and his skin was blackish. His eyes were very small, and he walked with a slight stoop, though gracefully as befitted a prince of the Church. He was less than thirty when he was made Bishop of Alexandria. He was a hammer wielded by God against heresy.

The small, dauntless man who saved the Church from a profound heresy, staying the disease almost single handed, was as astonishing in his appearance as he was in his courage. He was so small that his enemies called him a dwarf. He had a hook nose, a small mouth, short reddish beard which turned up at the ends in the Egyptian fashion, and his skin was blackish. His eyes were very small, and he walked with a slight stoop, though gracefully as befitted a prince of the Church. He was less than thirty when he was made Bishop of Alexandria. He was a hammer wielded by God against heresy.

There were other Fathers of the Eastern Church who wrote more profoundly or more beautifully, but none wrote with such a sense of authority or were so little plagued with doubts …. He wrote Greek as though those flowing syllables were lead pellets …. His wit was mordant. He did not often employ the weapon of sarcasm, but when he did, no one ever forgot it. When Arius, his great enemy died, he chuckled with glee and wrote off a letter to Serapion giving all the details of Arius’ death, how the heretic had talked wildly in church and was suddenly “compelled by a necessity of nature to withdraw to a privy where he fell, headlong, dying as he lay there.” As for the Arians, Athanasius hated them with too great a fury to give them their proper names. He called them dogs, lions, hares, chameleons, hydras, eels, cuttlefish, gnats, and beetles, and he was always resourceful in making them appear ridiculous …. At least twice Athanasius was threatened with death, and he was five times exiled. He was perfectly capable of riding up to the Emperor and holding the emperor’s horse by the bridle while he argued a thesis.

In the end he had the supreme joy of outliving all his enemies and four great emperors who had stood in his path, and must have known, as he lay dying, that he had preserved the Church …. It was a long triumph of one man against the world—Athanasius contra mundum! (pp. 67-68)