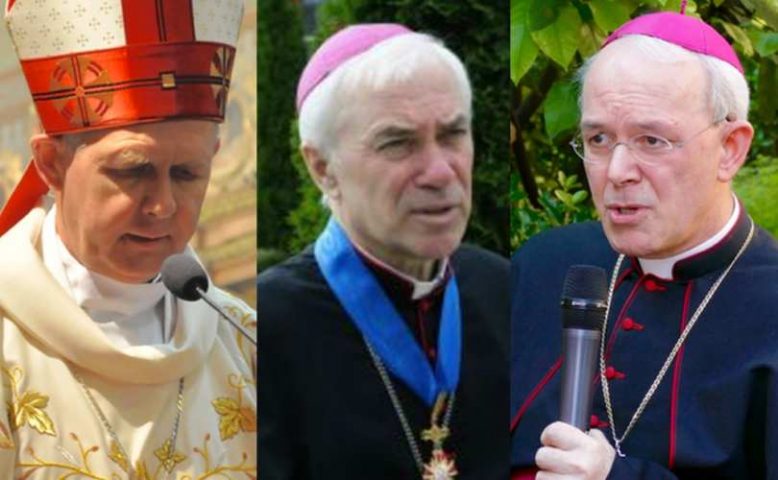

![]() As has been widely reported, three bishops in Kazakhstan – Tomash Peta, Jan Pawel Lenga, and Athanasius Schneider – issued a Profession of the Immutable Truths about Sacramental Marriage on December 31, 2017. This precisely reasoned defense of Catholic teaching on marriage gets to the heart of the problems occasioned by the eighth chapter of Amoris Laetitia.

As has been widely reported, three bishops in Kazakhstan – Tomash Peta, Jan Pawel Lenga, and Athanasius Schneider – issued a Profession of the Immutable Truths about Sacramental Marriage on December 31, 2017. This precisely reasoned defense of Catholic teaching on marriage gets to the heart of the problems occasioned by the eighth chapter of Amoris Laetitia.

Now that the initial flurry of commentary has died down, I’d like to examine calmly here three paragraphs that summarize why permission to receive Holy Communion given to people who are in “second marriages” and have the intention to continue to commit acts of adultery is a grave offense against Catholic teaching on the sacredness and indissolubility of marriage. This permission abolishes the perennial sacramental discipline that protects and upholds this teaching.

The Kazakh bishops write: “Sexual relationships between people who are not in the bond to one another of a valid marriage – which occurs in the case of the so-called ‘divorced and remarried’ – are always contrary to God’s will and constitute a grave offense against God.” This is plainly true. Adultery is never pleasing to God, is never authorized or tolerated by God, is always evil.

They continue: “No circumstance or finality, not even a possible imputability or diminished guilt, can make such sexual relations a positive moral reality and pleasing to God. The same applies to the other negative precepts of the Ten Commandments of God. Since ‘there exist acts which, per se and in themselves, independently of circumstances, are always seriously wrong by reason of their object.’ (John Paul II, Apostolic Exhortation Reconciliatio et Paenitentia, 17)”

This is a key point sometimes overlooked in the debate. Adultery can never be never “a positive moral reality and pleasing to God.” Therefore, the Church must never encourage people to engage in acts that are always per se offensive to God. It is pastorally deficient to advise that a person committing such evil acts may responsibly judge himself not to be guilty of giving serious offense to God due to alleged circumstances that diminish his culpability for his sins.

How can he be so sure of his innocence of his persistent mortal sin that he thinks God will not hold him to account, but rather wants him to receive the Holy Eucharist without repenting of his sin? And why would a priest advise someone that he may continue to commit the sin of adultery as long as that person thinks he will not be held guilty by God for that sin?

The priest’s job is to tell people not to sin, not to tell them to discover reasons why their sin is not sinful for them. It is an act of spiritual arrogance in God’s sight for the priest advisor or the civilly “remarried” person to claim that, because of some alleged exculpatory reason, he does not have to obey the Sixth Commandment now and in the future, and that he can worthily receive Holy Communion. We are called by Christ to conform our lives to God’s law, which includes the recognition by our intellect of the justice and holiness of that law.

The Kazakh bishops go on:

The Church does not possess the infallible charism of judging the internal state of grace of a member of the faithful (see Council of Trent, session 24, chapter 1). The non-admission to Holy Communion of the so-called “divorced and remarried” does not therefore mean a judgment on their state of grace before God, but a judgment on the visible, public, and objective character of their situation. Because of the visible nature of the sacraments and of the Church herself, the reception of the sacraments necessarily depends on the corresponding visible and objective situation of the faithful.

The canonical prohibition of the administration of the Holy Eucharist to those who “persist in manifest grave sin” (Canon 915) is based on the external action (in this case the contracting of a civil marriage and the ongoing cohabitation as man and wife). This cannot be set aside by any claim that a person judges himself to be inculpable of “manifest grave sin.” This canonical prohibition reinforces the moral guidance that the Church has always given in such cases: it’s perilous to one’s soul to violate God’s law, and it is a dangerous self-delusion to seek out reasons why that law does not oblige one’s obedience. Looking for excuses to keep sinning is not the way to fulfill God’s will in one’s life.

In an interview with The National Catholic Register, Bishop Athanasius Schneider summed up the matter: “The Church, for 2,000 years, always and everywhere unambiguously forbade people to receive Holy Communion while they lived more uxorio with a person who was not their legitimate spouse and who, at the same time, publicly formalized such a non-marital union and had no firm intention to stop such sexual relations. Since this universal practice of the Church touched an essential point of the sacraments, it has to be considered as irreformable.”

In another interview at the Rorate Caeli website, he defended the propriety of the Kazakh bishops raising these objections to Pope Francis in a spirit of Christian charity. His argument applies by analogy to any member of the faithful who turns to Pope Francis with his concerns about Amoris Laetitia and the subsequent developments:

When bishops remind the pope respectfully of the immutable truth and discipline of the Church, they don’t judge hereby the first chair of the Church, instead they behave themselves as colleagues and brothers of the pope. The attitude of the bishops towards the pope has to be collegial, fraternal, not servile and always supernaturally respectful, as it stressed (sic) the Second Vatican Council (especially in the documents Lumen Gentium and Christus Dominus). One has to continue to profess the immutable faith and pray still more for the pope and, then, only God can intervene and He will do this unquestionably.

So, fidelity and prayer – our sure hope in this troubled moment in the life of the Church.

_____________________