Female Athletes, Beaten By Boys, Claim Title IX Violation, by Charlie Butts, Billy Davis

June 25, 2019Report: Google Doing All It Can to ‘Prevent’ A Trump Repeat in 2020, by Jody Brown

June 25, 2019

By Fr. Alexander Lucie-Smith, Catholic Herald, 25 June, 2019

Contemporary evangelisation calls us to enter into a personal relationship with God. What better aid than the image of Our Lord’s wounded Heart?

God knows, better than anyone, what people are like, and the revelation of God is expressed in a way designed to help our frail human minds receive it.

Long before we were people of the book, we were people of the image. Before I could read, my favourite book was the Children’s Bible, and how I loved those pictures – Jonah and the Whale, Adam and Eve walking about in what looked like a greenhouse, and a green-eyed Jesus with flowing blonde locks teaching a group of attentive disciples.

But I was surrounded by images, growing up in the most Catholic country on earth. How I loved the statue known as Jesus the Redeemer – a royally robed and bleeding Christ, falling under the weight of his Cross; but above all, the object of many an afternoon walk, the statue of Our Lady of the Rosary, with Saints Dominic and Catherine on either side. I recently revisited that statue and was glad to see it exactly as I remembered it. Decades had passed but the memory of it had persisted, burned into my retina. I have read thousands of books, all of which have faded with time; but that image – never.

It’s false to say that the Catholic Church relied on images because people were mainly illiterate (in itself a questionable claim). The Catholic Church proposes images because this is something inherited from the Founder. For the greatest image is Jesus Himself. He is the image of the unseen God, as Saint Paul says in Colossians. God knows we need to see things, that is why He became incarnate in Jesus, so we can see God. Even the atheist Wittgenstein would agree with this. ‘Wir machen uns Bilder der Tatsachen’ he said. (Tractatus 2.2) ‘We make pictures of facts for ourselves’. Understanding is essentially pictorial. The Incarnation is not best understood as a propositional thing, but as a picture, a pictured fact, a Man.

Anyone thinking of embarking on a career of iconoclasm needs to ask whether they can think without images in their head. To do so would be very difficult and not a little boring; iconoclasm is an act, essentially, of lacerating self-harm.

But when talking or thinking of Jesus the Image, we might think it frustrating that we have no real idea of what he looked like, though pictures of the Lord all had certain commonalities, none of which are contradicted by the photograph-in-death that is the Turin Shroud in negative. That famous image was only revealed by the photographs taken by Secondo Pia on 28 May 1898, making him the first man for centuries to look upon what many believe to be the Saviour’s face. Devotion to the Holy Face has long been current, but the Shroud of Turin reveals the Holy Face in just the way the suffering twentieth century, soon to be born, needed to see it. But before the Shroud, and not replaced by it either, the image par excellence was that of Jesus on the Cross, displaying His Five Wounds, the fifth of which, that in His pieced side, reveals to the world His Sacred Heart.

The image of the Sacred Heart is an extrapolation of the Crucified’s image, in that the Heart is always shown as wounded. Thus, the origins of the devotion go back to the passage about the lance piercing Jesus’ side of which Saint John speaks in his Gospel: “but one soldier thrust his lance into his side, and immediately blood and water flowed out. An eyewitness has testified, and his testimony is true; he knows that he is speaking the truth, so that you also may (come to) believe.” (John 19:15-16). Moreover, the language of the heart of God, speaking to the heart of Israel, is foundational to the whole Hebrew Bible. Devotion to the Sacred Heart is deeply Biblical. This was something that Pius XII stressed in his encyclical Haurietis Aquas of 1956. In the same letter, the Pope dismissed the idea that the Sacred Heart was a devotion for the sentimental and the ignorant, something I hope I have also done with my Wittgensteinian excursus above.

Devotion to the Sacred Heart should not seem old fashioned today, because contemporary evangelisation calls us to become intentional disciples, that is, to enter into a personal relationship with God. In such a relationship, it is not mind speaking to mind, but heart speaking to heart. The time is ripe for a revival in the devotion, not that it ever really went away. Once you start to look out for them, images of the Sacred Heart are everywhere – certainly in all churches, and in many homes as well.

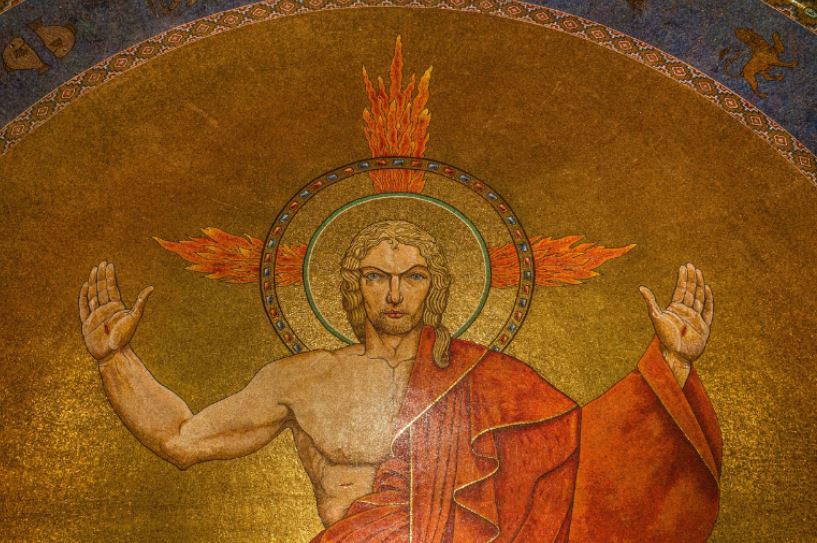

One of the most famous is to be found in a side chapel in the Gesú, the Jesuit Church in Rome. (The Jesuits, from their start, were propagators of the devotion.) The picture of Jesus displaying His Sacred Heart is by Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787), a great artist, but it is, I think, his only bad picture, and too saccharine for modern tastes. Far more effective is the great apse mosaic of Sacre Coeur in Paris, where Christ is seen as both majestic and welcoming. That mighty church was built as a national act of reparation by the French to atone for the sins of the nation. Its interior is perhaps the living vindication of the devotion – it is always full of people, and not tourists alone, but people praying in front of the Blessed Sacrament, which has been continually exposed there since 1st August 1885. Even a cursory visitor will notice how the people drawn to the Basilica are from every nation under the sun, and how the confessionals are busy too. Here, before the image of Jesus with His Sacred Heart open to all, the Church is truly seen as Catholic. Here the concept of atonement for sins against the Sacred Heart is also the place of ‘at one ment’ of all peoples. We come to unity in and through the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

The great mosaic in Sacre Coeur, inaugurated at Pentecost 1923, has a somewhat Eastern feel to it, recalling the great mosaics of, for example, Monreale, and other Byzantine-influenced churches of yesteryear. Once, in the tiny and ancient Orthodox Church of St Mary of the Mongols in Istanbul, I came across a picture of the Sacred Heart among the many icons that lined its walls, which reminded me that this is primarily a Western and Latin devotion, though it has in fact spread to the particular Churches of the East that are in communion with Rome. The Sacred Heart emphasises the loving humanity of Christ, and as such may well be seen as part of a ‘low’ Christology, while the depiction of Christ in Majesty so beloved of the East may be seen as part of a ‘high’ Christology; one emphasises the humanity, and the other the divinity of Christ. But in truth the Sacred Heart should be seen as a bridge between the two poles of Christology: Jesus in His sacred humanity is the revelation of His divinity: this is the truth of the Incarnation – God becoming like us to make us like Himself.

https://catholicherald.co.uk/commentandblogs/2019/06/25/the-time-is-ripe-for-a-revival-in-devotion-to-the-sacred-heart/